We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Re-watering the Prairie

Montana stream restoration project imitates beavers to spread water, expand riparian habitat

Traversing dirt roads in Montana’s undulating prairie landscape on a hot summer day is an exercise in avoiding deep ruts, while watching the horizon for oncoming thunderstorms that might strand a driver in the slick clay soil. Water here is precious and essential for life—but also can arrive in destructive flows, sometimes flooding and sometimes sliding the foundation out from under highways.

Prairie streams—vital ribbons of water and riparian habitat for wildlife—graphically demonstrate the power of erosion. Once, numerous beaver dams slowed water flowing through these drainages, but beavers were nearly wiped out in the heyday of the fur trade. As a result, the water runs faster, forming narrowing stream channels that become disconnected from the surrounding lands. This reduces both water availability and the riparian habitat that is essential for the survival of many prairie species, including the iconic Greater Sage-grouse.

The National Wildlife Federation, in partnership with the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, is taking steps to improve riparian conditions on prairie streams in north-central Montana, using low-tech methods that include beaver dam analogs (also known as BDAs) to imitate beaver activity and expand the diversity of flora and fauna. This approach to restoration is expanding around the western U.S., sometimes combined with relocation of beavers from other areas. In Montana, where relocation is not a favored management strategy, improving stream conditions with BDAs facilitates natural recolonization by beavers already living in the area.

With core funding from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and additional financial and in-kind support from diverse partners ranging from Defenders of Wildlife to the Montana Trappers Association, (as well as private donors and foundations), this three-year project is focused on slowing water and creating wet meadows on priority sage-grouse habitat. This will provide important food sources and protective cover for vulnerable sage-grouse chicks in dry summer months, helping to support species recovery.

In short, says ecologist Amy Chadwick of Great West Engineering, who is leading the project design and implementation, “we’re putting water back on the floodplain to keep green areas green for longer.”

One project site at Cottonwood Creek, a drainage on public lands north of the Missouri River, illustrates the power and promise of this deceptively simple restoration technique. A Montana Conservation Corps (MCC) young-adult crew camps on the ridge high above the creek bottom, and is joined early each morning by field staff and seasonal staff with the Bureau of Land Management as well as the National Wildlife Federation’s staff, contractors, and volunteers.

The team tackles this transformative work with humor and enthusiasm, despite punishing heat, steep terrain for moving materials from a staging area to the creek bottom far below, and boot-sucking, slippery mud.

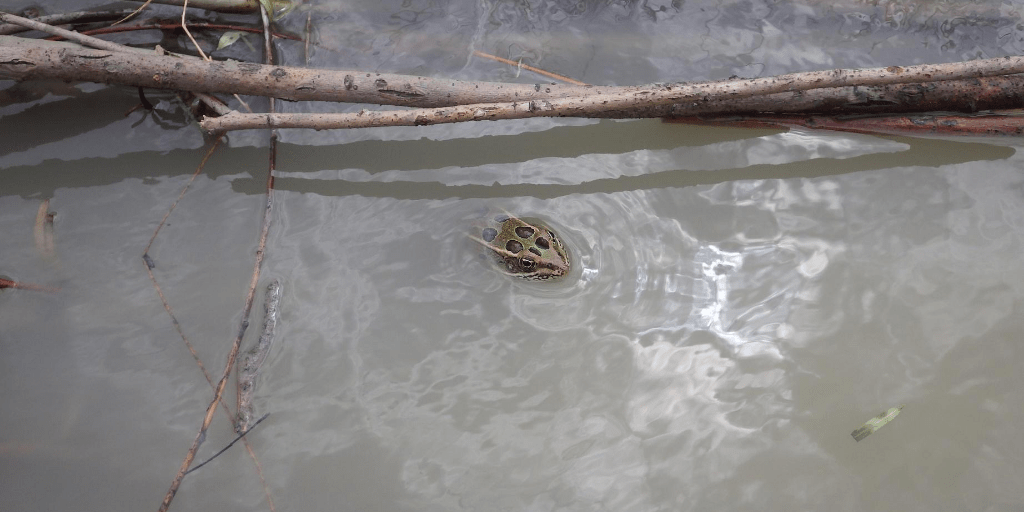

Results are apparent almost immediately. After just one day of BDA construction, water that previously rushed down the narrow channel is already spreading onto the surrounding floodplain, glistening under bright yellow sunflowers and drawing leopard frogs out onto newly watered ground. As team members pack up to leave the site several days into the project installation, they watch from the hill as a muskrat wanders downstream and plops from the bank into a newly formed pool, swimming large circles in a channel that didn’t provided this habitat just a day earlier.

“It’s stacking up and spilling more water than we anticipated, after just three days,” Chadwick notes. “We’re pioneering low-tech restoration approaches proven effective in other parts of the West in a new landscape. It’s very exciting to try out a lot of different things to see what works and what doesn’t.”

In fact, learning about what works and what doesn’t is a primary project goal. Thanks to a collaborative monitoring project led by the University of Montana and the U.S. Geological Survey, researchers are tracking surface water presence and temperature, instream habitat characteristics, aquatic vertebrate communities, and riparian vegetation coverage and composition. Additional research by the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute is tracking bird diversity as well.

This monitoring information will help us understand how these restoration techniques change stream and riparian habitat, which will in turn inform future restoration efforts—as well as build trust and confidence among local landowners and resource managers.

Learning about what works and what doesn’t is a primary project goal.

“I’m glad you describe this as experimental,” remarks BLM Malta Field Manager, Tom Darrington as he visits the Cottonwood Creek site with several staff members, noting that a commitment to learning is an important part of a collaborative project like this. Tom Probert, BLM North Central District Hydrologist, agrees that we’ll build acceptance by showing improvement on the ground and by engaging diverse partners. “I’m excited that we’re trying new things here,” he says, and then turns back to work.

To learn more about beaver mimicry and other low-tech restoration techniques, check out these resources:

- How Beavers Boost Stream Flows (NWF blog)

- Nature’s Ecosystem Engineers (National Wildlife magazine)

- Low-Tech Process Based Restoration (Utah State University)