We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Enlisting farms, fields, and forests in the fight against climate change, part 2

Part 2: Biodiversity and ecosystem integrity concerns

From forests to fields and from ranches to rooftop gardens, working lands can play a role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. In Part 1 of this blog series, we talked about various incentives that are being offered to encourage landowners and producers across the country to scale up their efforts to reduce emissions and enhance carbon storage. These include voluntary conservation programs administered by the US Department of Agriculture, long-term conservation easements, and carbon markets.

It doesn’t matter what form these incentives take–if they’re not designed carefully, they can pose concerns to social equity, as discussed in Part 1, and to biodiversity, which we dive into here. Biodiversity conservation and climate mitigation can work in tandem, but it shouldn’t be assumed that what’s good for the climate is always good for biodiversity.

Even well-intended incentives can encourage a narrow focus on carbon sequestration and storage at the expense of other desirable ecosystem services or functions, like wildlife habitat or aesthetic and recreational value of land. Some incentives could even encourage activities that harm wildlife by eliminating or degrading important habitat.

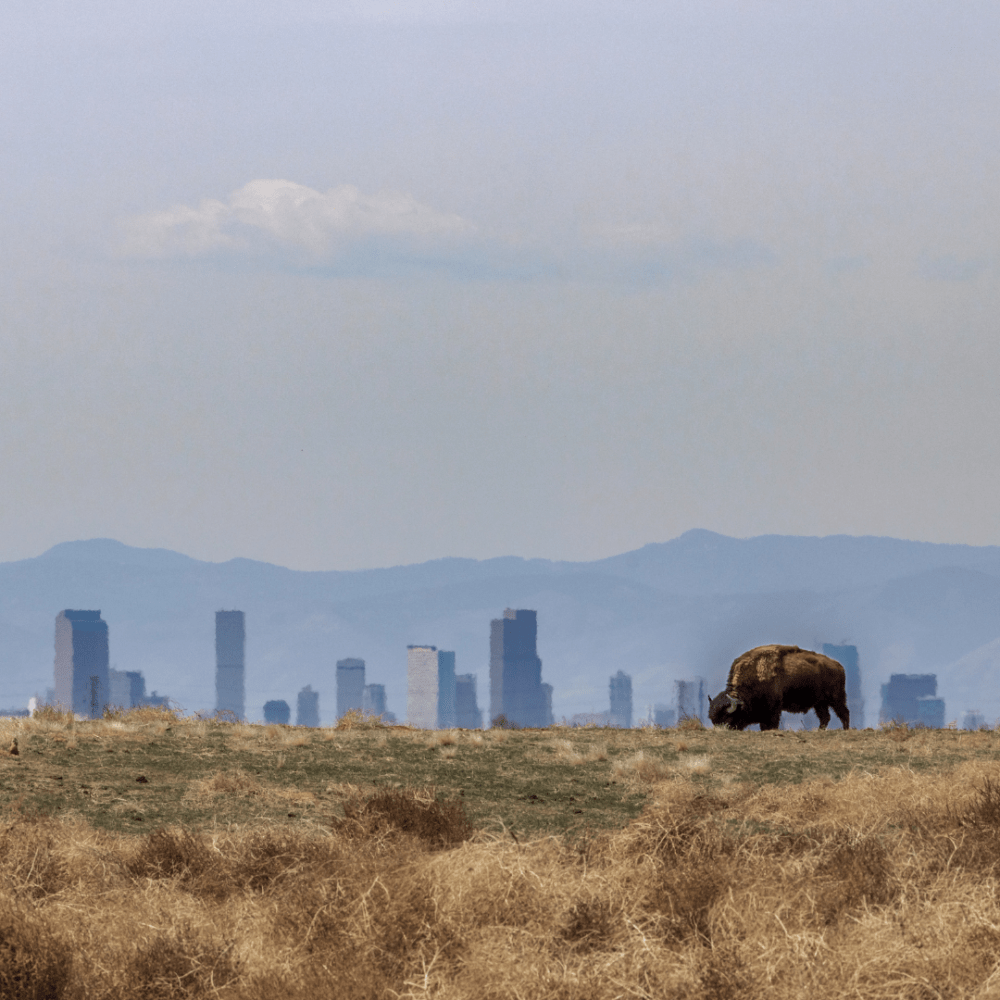

For example, incentives could inadvertently encourage landowners to convert or degrade native grasslands in order to plant trees. Although there has been a great deal of enthusiasm in the last decade around tree planting to drive rapid carbon uptake, such efforts frequently overlook the values of grasslands and of planting vegetation native to an area. Grassland ecosystems store the majority of their carbon underground where it is safe from loss due to fire and stabilized by plant root systems. In the US, grasslands provide critical habitat for animals, including shorebirds who nest in the Prairie Pothole region, songbirds such as the Western meadowlark, and iconic mammals such as bison and pronghorn. Yet grasslands are the most imperiled terrestrial ecosystems on the planet, and conversion of these ecosystems continues at an alarming rate in the U.S., disappearing faster than the Amazon rainforest–driven in part by the misguided attempt to address climate by planting corn for ethanol, which only results in greater climate emissions. As a result, North American grassland bird populations are declining precipitously.

To avoid negative outcomes related to biodiversity, policymakers should:

- Think beyond carbon and structure incentives with multiple goals in mind. Incentives should be structured to include sufficient safeguards to prevent conversion of native ecosystems, and to reward activities with co-benefits to soil, water, and biodiversity. Policies should also be designed to encourage projects that support climate change adaptation and resilience.

- Seek to optimize, not maximize, carbon sequestration and storage. Recognize the trade-offs between near-term and long-term carbon sequestration and storage. Similarly, realize that short-term increases in carbon emissions as part of climate-informed management strategies can help to reduce overall emissions in the future. For example, prescribed burning of a forest understory could result in a pulse of emissions in the near-term, but in the medium-term, it could insulate the forests from extreme fire and an even larger pulse.

- Structure incentives and regulations to prevent the spread of invasive species. Fast-growing plant species that spread easily and tolerate a broad range of conditions may be great at sequestering carbon, but these same traits can help them to outcompete native species. Ensure that any efforts to increase carbon storage and sequestration don’t harm native ecosystems by introducing new invasive species.

There’s no doubt: family farmers, ranchers, and forest landowners have a role to play in addressing climate change.

When thoughtfully designed and implemented, natural climate solutions can complement efforts to restore landscapes, enhance the resilience of both human communities and natural ecosystems against disasters, and support thriving wildlife populations. Yet without careful planning and evaluation, activities intended to support climate change mitigation could come at the expense of these goals.

As policymakers seek to motivate farmers, ranchers, and forest landowners to continue to lead in curbing emissions, safeguards for both equity and biodiversity will be essential elements of any incentive.

Special thanks to Ben Knuth for his helpful feedback and contributions on this blog series.