We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Southeast Sportfish: Why I Care About What They Eat

In my home state of Georgia, coastal anglers prize sportfish like bull redfish, tarpon, cobia, amber jack, snapper, sea bass, sea trout, and grouper.

Many Southeast sportfish are voracious eaters, preying on nearly anything that crosses their path, but forage fish – small, schooling fish like herring and shad (and other indigenous forage fish) – are an important part of their diet. And that brings me to why I care about what they eat: my big concern is to be a good steward of the food chain. If trophy fish don’t have enough prey to feed on, their populations suffer.

These days, sportfish have plenty of competition for forage fish, which are also harvested in rapidly increasing quantities to service an ever-growing demand for products like fish oil, fertilizer, aquaculture and livestock feed, cosmetics, and pet food.

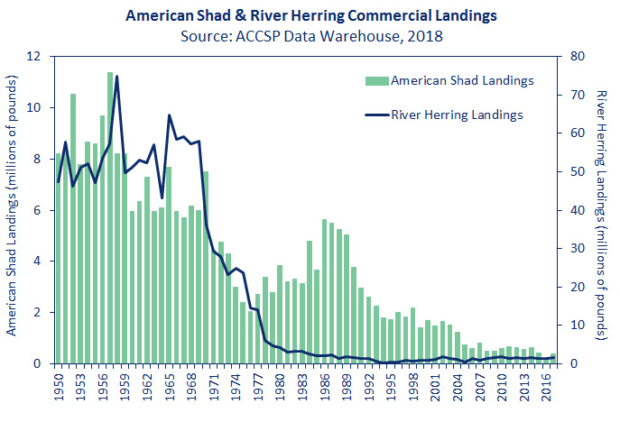

Here along the Atlantic Coast, there is perhaps no better example than that of shad and river herring to illustrate this mounting demand. Shad and river herring (a general term which encompasses both alewife and blueback herring) spend much of their lives offshore, but to spawn each year they swim up Atlantic Coast rivers and streams to freshwater. These were once robust stocks, supporting commercial and recreational fisheries for many decades and seeming for a time to be inexhaustible. However, decades of overfishing, coupled with destruction and fragmentation of shad and herring’s freshwater spawning habitats have caused dramatic declines in these populations. Despite Atlantic State efforts to curtail fishing and restore in-river habitat, populations have not rebounded.

Contributing to the problem, river herring and shad are not managed under the federal Magnuson-Stevens Act, and as such still do not have catch-limits set in federal waters, where they are caught in huge quantities as bycatch in other fisheries that account for the needs of other species (like bull redfish and tarpon) up the food chain.

Unfortunately, many forage fish species are in the same boat, and either do not currently have science-based catch limits set for their harvest in offshore waters, or have limits set which do not account for the needs of other marine species that rely on forage fish. The end result? Dramatic declines akin to what occurred with river herring and shad, with effects that reverberate through the marine food web. To ensure healthy coastal sportfish populations, we need to find a way to ensure the stability of the forage fish they rely upon. It’s an economic priority too: the forage fish that feed prized sportfish species are critical to Georgia’s coastal economy. Annually, state anglers generate billions in retail sales and related spending.

Bipartisan legislation introduced in Congress would apply some common-sense steps to conserve forage fish and their critical role in the food chain. The Forage Fish Conservation Act (H.R. 2236) would improve how forage fish are managed, including by:

- Providing a national, science-based definition for forage fish in federal waters;

- Assessing the impact a new commercial forage fish fishery could have on existing fisheries, fishing communities, and the marine ecosystem prior to the fishery being authorized;

- Accounting for predator needs in existing management plans for forage fish;

- Specifying that managers consider forage fish when establishing research priorities;

- Ensuring scientific advice sought by fishery managers includes recommendations for forage fish;

- Conserving and managing river herring and shad in the ocean; and

- Preserving state management of forage fish fisheries that occur within their jurisdiction

Conservationists understand the responsibility to steward our natural resources – for today, and for future generations. That includes the trophy sportfish species and the prey upon which they rely, like forage fish.