We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Protecting the Christmas Goose—One Step Forward and Two Steps Back

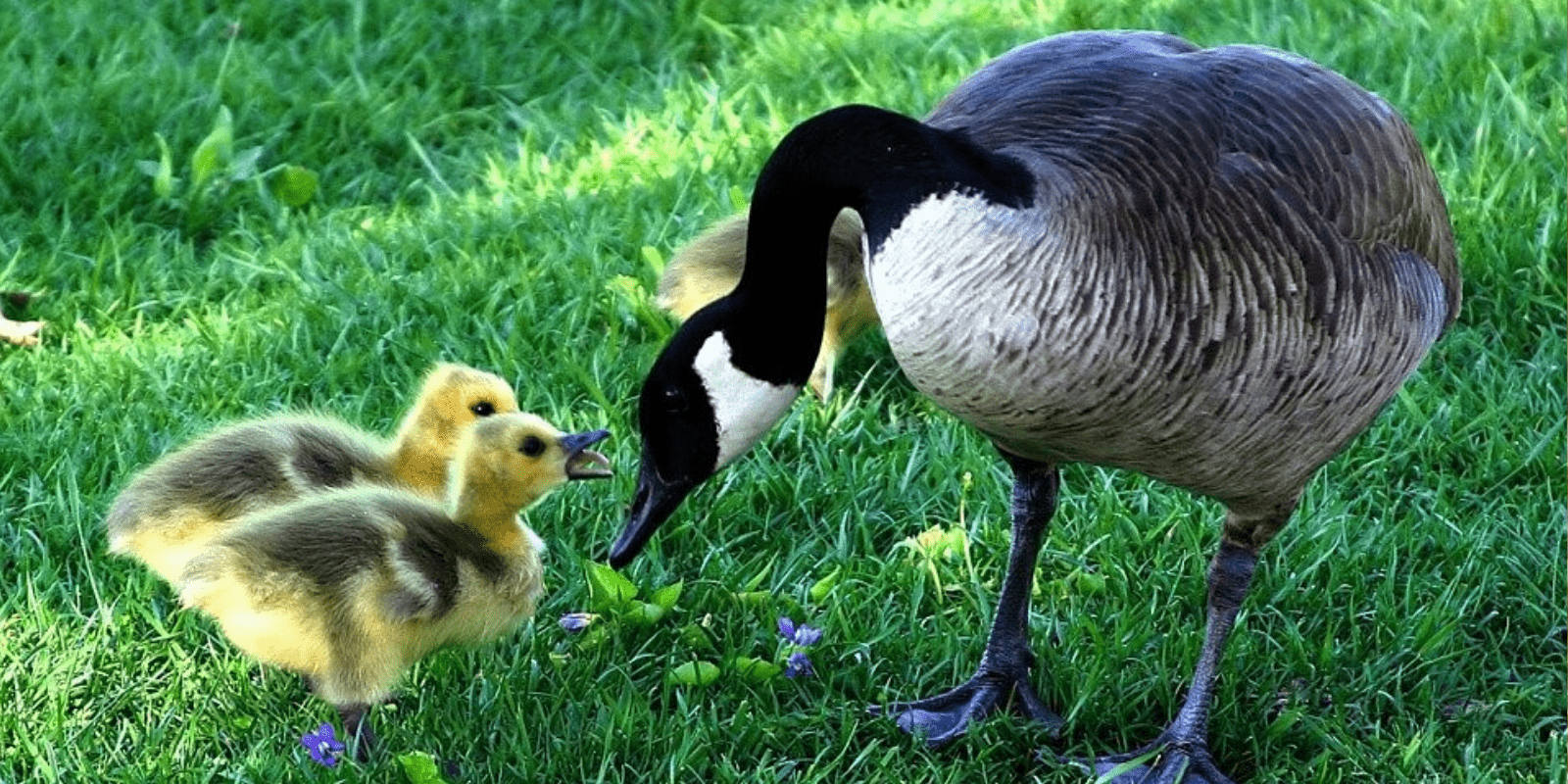

For centuries, the Christmas goose was a staple holiday dish both in Europe and the United States. The old English nursery rhyme recounts, “Christmas is coming, the geese are getting fat.” Geese were plentiful, affordable, and readily available in the fall, just in time for the holidays.

It wasn’t until around 1843 when Charles Dickens wrote “A Christmas Carol,” in which Scrooge gifted the poor Cratchit family with a grand turkey—rather than a traditional goose—that the idea of serving turkey for Christmas started to catch on in England.

When colonists arrived in North America, they found an abundance of Canada geese, making the bird a popular food item in the United States, as well. But, colonial-era hunting and widespread consumption of the goose caused major declines in its population. Declines of bird species like this led to the creation of laws like the Migratory Bird Treaty Act that, among other things, makes it illegal to hunt, kill, sell, or purchase migratory birds without a valid Federal permit. Today, many of the geese still eaten in the United States are domesticated and farmed.

Although no longer a common symbol for the holiday, especially in the United States, geese now serve as an emblem for successful conservation.

A Honking Good Conservation Story

Like the turkey, the Aleutian cackling goose is an example of a species that made a remarkable recovery with the help of conservation efforts that spanned more than thirty years and three continents.

The Aleutian cackling goose, a small subspecies of the cackling goose, breeds on Alaska’s Aleutian Islands and winters in parts of California and Oregon. Until the 1830s, this species was found throughout the outer Aleutian Islands, and its population was estimated to be in the thousands.

In 1967, however, the Aleutian cackling goose was listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966 because of a drastic population decline. The primary cause of this decline was the introduction of non-native arctic foxes for the fur industry. The foxes preyed heavily on the Aleutian cackling goose and its nests, and as of 1967, only an estimated 790 Aleutian cackling geese remained.

Biologists with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) saw the need for immediate action and developed an unprecedented collaborative effort with state governments, private landowners, and organizations to bring this species back from the brink of extinction. Thanks to long-term, cooperative conservation efforts, such as fox removal, translocation of captive birds, and captive breeding programs, as well as laws like the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, the Aleutian cackling goose population jumped to an estimated 37,000 birds by 2001—nearly five times greater than the USFWS’s recovery goal.

That same year, the USFWS stated that the Aleutian cackling goose no longer required listing under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, making this a true conservation success story.

Waddling it Back

Despite the power of these conservation laws, the Trump administration is now taking a major step backward by undermining the Migratory Bird Treaty Act—putting this recovered species, and many other vulnerable bird species, at risk.

In 2017, the Department of the Interior released an unprecedented legal opinion stating that any “incidental” take of migratory birds, including cackling geese, will not be enforced under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

This change to how the Migratory Bird Treaty Act is enforced allows birds to be killed at any time, by any means, or in any manner—as long as the purpose is not specifically to kill birds. For many bird populations, this exception to the Act could be detrimental as it essentially says that this bedrock law will no longer be enforced except when it can be proved that any killing of a migratory bird was intentional.

Seventeen former, high-level Department of the Interior officials have already railed against this rollback, saying that it “needlessly undermines a history of great progress, undermines the effectiveness of the migratory bird treaties, and diminishes U.S. leadership.”

In order to put a stop to the nearly 30 percent decline in bird populations we’ve experienced over the last 50 years, we need to increase our protections for migratory species, not decrease them.

We urge Congress to step up and take action to help ensure that species like the sandhill crane, wood duck, and snowy egret—all species that the Migratory Bird Treaty Act helped save—remain around for generations to come.

Take Action!