We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Harnessing Natural Infrastructure to Protect the Built Environment

A Podcast by National Wildlife Federation and Allied World Assurance Company

The National Wildlife Federation (NWF or Federation) and Allied World share ten years of partnership to raise awareness about the role nature-based solutions can play in hazard risk reduction. In their latest collaboration, NWF and Allied World produced a podcast, Harnessing Natural Infrastructure to Protect the Built Environment, that discusses findings from their newest report, The Protective Value of Nature. This report builds on two previous reports published by NWF, Allied World, and other partners: Natural Defenses from Hurricanes and Floods (2014), and Natural Defenses in Action (2016).

The podcast features Federation and Allied World experts who discuss the latest science and benefits of natural defenses, provide examples of natural approaches implemented across the United States, and address how a wide range of stakeholders including property owners, developers, community planners, and others can utilize natural infrastructure to protect the built environment. Below, we summarize some of the podcast highlights. To listen to the full podcast, please click here.

Climate Change Increases Natural Disaster Frequency and Intensity

The podcast begins by addressing a costly reality: across the nation, natural disasters take an enormous ecological, social, and economic toll. Since 2010, the United States has experienced more disasters with damages over one billion dollars than in any prior decade.[1] Ron Killian, Allied World’s Senior Vice President, Catastrophe Modeling, states that 2021 was the second costliest year for insurance companies ever – Hurricane Ida alone caused an estimated $65 billion in damages, of which $36 billion was insured. As climate change increases natural disaster risks in severity and frequency, Killian reminds listeners that continued coastal population growth exerts strong pressure on coastal environments and compromises natural habitats.

Traditional Structural Approaches Compared to Natural Infrastructure

There is mounting evidence that natural and nature-based approaches can often be more effective and less expensive in the long-term than conventional structural approaches to safeguard communities, reduce risk, and provide numerous co-benefits.

“Natural infrastructure” refers to intact or restored systems, such as wetlands, forests, and coral reefs, and “nature-based” approaches are designed and constructed by people to mimic natural systems, like green roofs. In contrast, traditional structural approaches (i.e., “grey” or “hard” infrastructure) refer to human-made structures like dams, levees, seawalls, and bulkheads. Podcast guests also include fire suppression, fire breaks, and air conditioning in our understanding of what constitutes “traditional” infrastructure.

NWF’s Senior Scientist of Climate Adaptation, Patty Glick, highlights that the United States has historically fought against nature by hardening shorelines, straightening rivers, suppressing fire, and cutting down urban trees to make way for development. These conventional approaches can sometimes do greater harm than good. Studies show that paving surfaces, filling wetlands, and armoring coastlines increase or relocate, rather than decrease, flooding and erosion.[2] Glick provides the example that “beaches often become more eroded in front of seawalls,” harming wildlife habitat and reducing recreational opportunities. Additionally, Glick points out that much of the country’s existing grey infrastructure is in poor condition and is not designed to withstand increasingly severe climate hazards. In the American Society of Civil Engineers’ most recent report card, both dams and levees received “D” grades,[3] indicating a significant amount of economic investment needed for updates and repairs. While podcast guests agree that grey infrastructure is necessary to safeguard people and property in some places, the degradation of ecological services and the cost of continual maintenance can outweigh the potential benefits.

Natural Infrastructure Builds Community Resilience

Dr. Bruce Stein, Chief Scientist and Associate Vice President for NWF, states that “protecting the remaining natural systems that we have is one of the most cost-effective approaches for ensuring that our communities take advantage of natural defenses.” Natural systems are well adapted to natural disturbances and have the capacity to withstand and recover from hazards better than human-made structures.

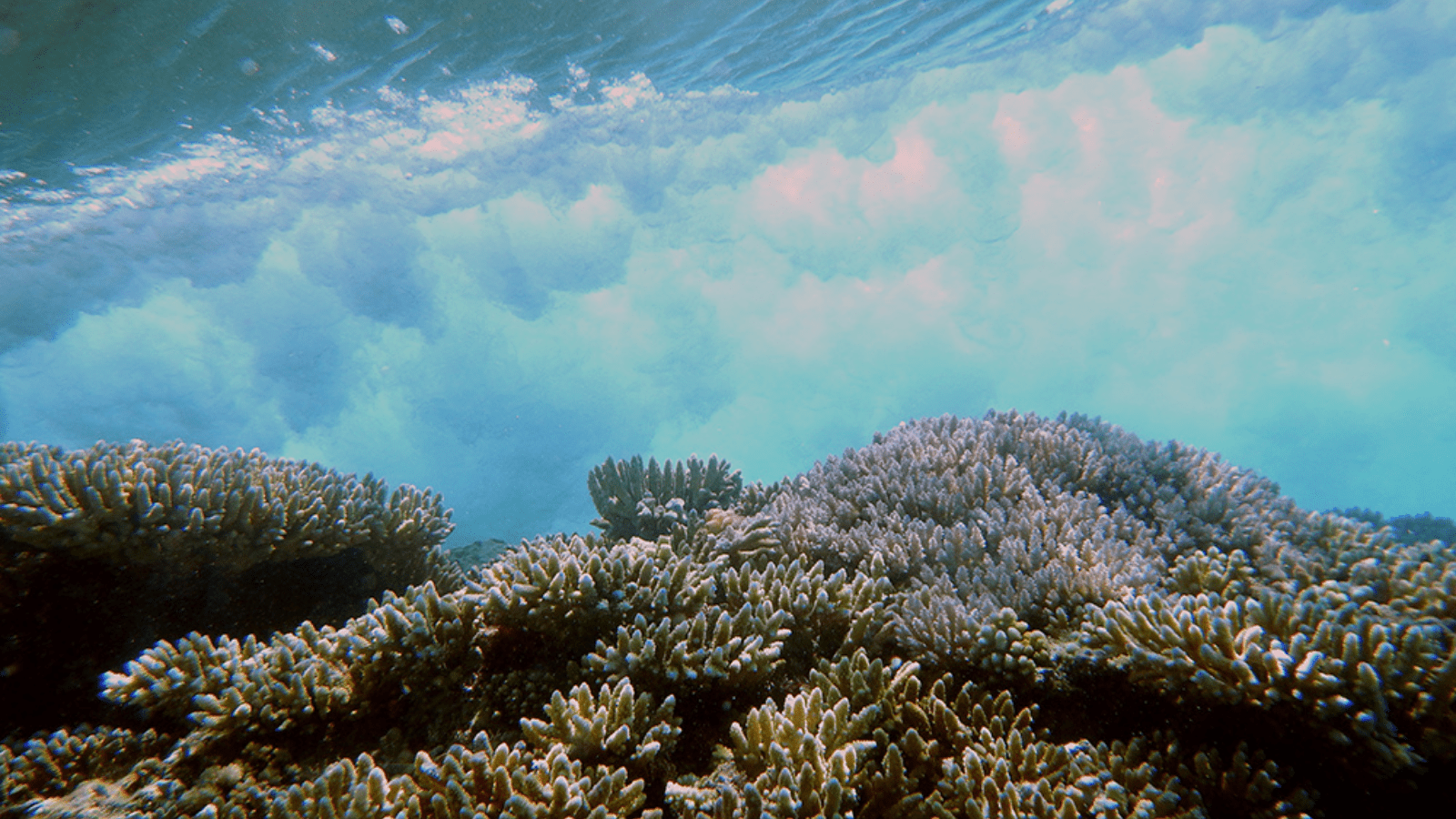

There is a growing body of empirical evidence that shows just how well natural infrastructure reduces damages compared to areas without those features. For example, Glick shares that a recent meta-analysis, “suggests that [coral reefs] reduce wave energy by an average of 97% compared to areas without coral reefs.” In addition, marshlands reduce wave height by 70% or more, and trees reduce urban heat stress by as much as 13%.[4] Along the Gulf Coast, the estimated benefit-cost ratio of wetland restoration for flood risk reduction is 8:1, compared with only 0.99:1 for local levees in high-risk areas.[5]

Natural infrastructure provides communities with a wealth of ecosystem services and co-benefits, such as improving water quality and recharging groundwater, supporting fish and wildlife habitat, reducing erosion, sequestering carbon, and providing aesthetic and recreational opportunities.[6] Dr. Stein adds that “protecting and restoring natural systems and providing better access to them dramatically improves quality of life for residents.” All of these benefits contribute to enhancing a community’s hazard resilience. As podcast host, Allied World’s Senior Vice President, North America Environmental Division, Helen Eichmann agrees that natural approaches are a “classic win-win” both to protect wildlife habitats and to reduce hazard risk for communities.

Advancing Natural Infrastructure Solutions

Natural infrastructure projects are adaptable, and can fit a wide variety of budgets, landscapes, and timelines for a diverse set of stakeholders. Patrick Fitzgerald, NWF’s Senior Director of Community Wildlife Program, emphasizes that property owners, developers, community planners, and others across the nation are evaluating existing infrastructure and strategizing how they can use natural and nature-based approaches to enhance resilience and protect the built environment, whether through larger or smaller-scale projects.

Fitzgerald shares that the Broadlands Homeowner’s Association in Loudoun County, Virginia, goes beyond simple compliance with federal and state regulations by creating a long-term habitat maintenance plan, a community nature center, and a committee that supports conservation landscaping. Fitzgerald highlights NWF’s Community Wildlife Habitat Program and projects like bioswales and rain gardens as examples of how communities can integrate smaller-scale nature-based systems into the landscape to enhance ecological benefits and improve climate resiliency.

While the recently enacted Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act provides an unprecedented amount of attention and funding to natural infrastructure, podcast guests discuss the need for additional research and resources for stakeholders to implement nature-based solutions and emphasize the importance of meaningful engagement with local communities when developing such solutions. Dr. Stein, Glick, and Fitzgerald reiterate the necessity to protect existing natural systems and to integrate the use of natural infrastructure to enhance resilience and hazard mitigation within our built environment.

More work needs to be done to remove existing barriers and to increase accessibility to natural infrastructure solutions. To learn more about natural and nature-based solutions, please click here to listen to the full podcast episode, and click here to read The Protective Value of Nature.

[1] NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). 2020. Billion-dollar weather and climate disasters: Table of events. Silver Spring, MD: NOAA (accessed May 18, 2020). https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/events

[2] ASFPM Riverine Erosion Hazards Workgroup. 2016. ASFPM Riverine Erosion Hazards White Paper. Madison, WI: ASFPM; Christin, Z., and M. Kline. 2017. Why We Continue to Develop Floodplains: Examining the Disincentives for Conservation in Federal Policy. White paper. Tacoma, WA: Earth Economics; Heine, R.A., and N. Pinter. 2011. Levee effects upon flood levels: An empirical assessment. Hydrological Processes 26: 3225–3240; Ogden, F.L., N. Raj Pradhan, C.W. Downer, and J.A. Zahner. 2011. Relative importance of impervious surface area, drainage density, width function, and subsurface storm drainage on flood runoff from an urbanized catchment. Water Resources Research 47: W12503.

[3] ASCE (American Society of Civil Engineers). 2021. 2021 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure: A comprehensive assessment of America’s infrastructure. Reston, VA: American Society of Civil Engineers (accessed April 8, 2022). https://infrastructurereportcard.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/National_IRC_2021-report.pdf.

[4] Garzon, J.L., M. Maza, C.M. Ferreira, J.L. Lara, and I.J. Losada. 2019. Wave attenuation by Spartina saltmarshes in the Chesapeake Bay under storm surge conditions. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 124: 5220–5243; Zölch, T., J. Maderspacher, C. Wamsler, and S. Pauleit. 2016. Using green infrastructure for urban climate-proofing: An evaluation of heat mitigation measures at the micro-scale. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 20: 305–316. Review of the Effectiveness of Natural Infrastructure for Hazard Risk Reduction.

[5] Reguero, B.G., M.W. Beck, D.N. Bresch, J. Calil, and I. Meliane. 2018. Comparing the cost effectiveness of nature-based and coastal adaptation: A case study from the Gulf Coast of the United States. PLoS One 13: e0192132.

[6] Costanza, R., R. de Groot, P. Sutton, et al. 2014. Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Global Environmental Change 26: 152–158.