We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

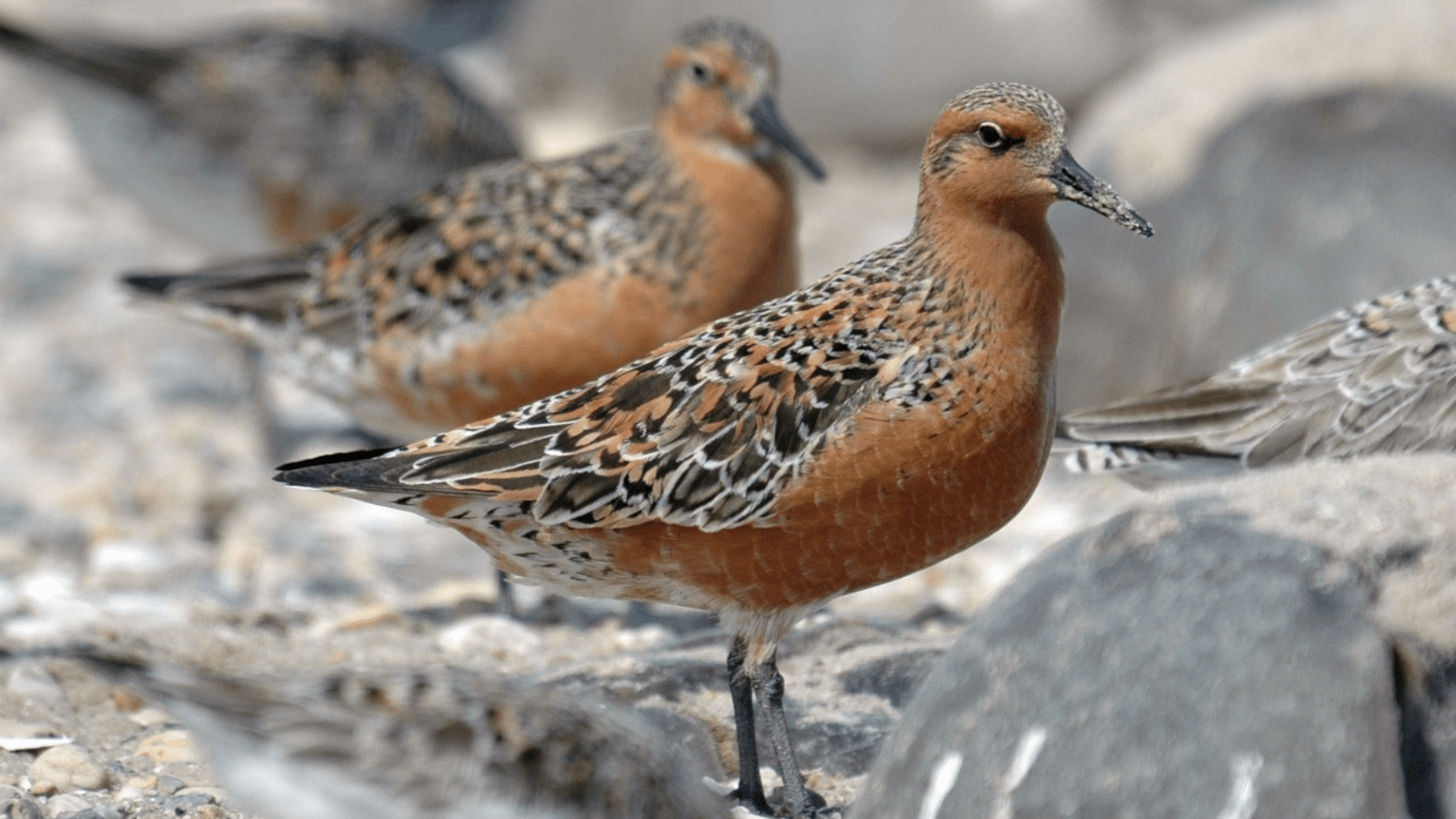

Synchronous Survival: Red Knots and Horseshoe Crabs

A millennia-long, delicate balance is being upended by threats to horseshoe crabs on the Delaware Bay’s beaches

Every year toward the beginning of May, in one of the great confluences of nature, red knots migrating from the southern tip of South America descend upon Delaware Bay in the tens of thousands, right as horseshoe crabs lay eggs upon the bay’s beaches. Red knots, a shorebird named for its distinguishable reddish breast and face, travel from Tierra del Fuego to the Canadian Arctic and back every year, a trip totaling over 18,000 miles.

While flying north from South America, red knots can remain airborne for up to a week straight, burning stored energy and losing substancial amounts of body mass in the process. The eastern Atlantic seaboard, specifically Delaware Bay, serves as the crucial midway point for this migration, where red knots rest and replenish before starting the second leg of their journey.

During this two to three-week stop, red knots must increase their fat stores (often doubling their weight) in order to complete the journey and successfully breed in the Arctic. That is why horseshoe crab eggs are essential to the survival of the red knots. These eggs are readily accessible and filled with fat, essentially a “superfood”, perfect for these famished birds on a tight schedule.

Tough competition

This millennia-long, delicate balance is being upended by threats to the horseshoe crab and its ability to reproduce on the Delaware Bay’s beaches. Horseshoe crabs face threats from both habitat loss and overharvesting. Development along the coastline reduces available acreage and can create pollution while powerful storms like Hurricane Sandy erode the beaches.

In addition to increasing the strength of storms, climate change has increased water temperatures in the bay, in some years causing horseshoe crabs to lay eggs earlier in the season, which upsets the synchronization with red knots.

In recent decades, horseshoe crabs have seen a dramatic rise in harvesting for use as bait and use in the pharmaceutical industry. Horseshoe crabs provide a cheap and accessible form of bait for whelk and eel fishing. In the span of five years during the 1990s, horseshoe crab harvesting skyrocketed from 100,000 to 2.5 million per year.

In addition to their use as bait, horseshoe crab blood contains a unique protein used for pharmaceutical vaccines and medical devices to detect the presence of potentially harmful endotoxins. Pharmaceutical companies have agreements with several states allowing for the temporary capture of horseshoe crabs with the promise of releasing all horseshoe crabs once the blood has been drawn. However, this practice has come under scrutiny for excessive horseshoe crab deaths, the secrecy of the operation, and the availability of an artificial alternative.

Since 2020, environmental groups have had lawsuits pending against Charles River, a pharmaceutical company that harvests 150,000 horseshoe crabs annually, arguing that their horseshoe containment facilities in South Carolina have a fatality rate of 20-25%. These groups claim that by depleting the horseshoe crab population, Charles River is denying red knots their primary food source in the region and this constitutes a violation of the red knot’s federal protections under the Endangered Species Act.

Charles River states that the fatality rate is only 5%, yet research from South Carolina’s Department of Natural Resources identifies the mortality rate as 20%. These lawsuits will play a crucial role in determining the protections for horseshoe crabs going forward. In the meantime, both the National Wildlife Federation and the South Carolina Wildlife Federation have called for male-only harvest, implementation of best-management practices, and the adoption of the synthetic alternative, which is already in use by the pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly.

The consequences of the horseshoe crab decline are severe for the red knot’s wellbeing. In the late 1980s, observers counted the red knot population in the Delaware Bay at 99,000. After Hurricane Sandy, when 70% of New Jersey’s prime horseshoe crab habitat was washed away, red knots were listed as threatened. Yet their downward trend continued with their numbers falling to 19,000 in 2020 and in 2021 plummeting to just 6,800. Red knots don’t have the luxury of waiting for action. Several more bad years for horseshoe crab eggs risks the survival of red knots. One of the best ways to protect these migratory birds is to ensure their food source is abundant and reliable, and the best time to take action is now.

Even with harvesting limitations, coastal development guidelines, beach habitat restoration and volunteer-supported monitoring, it will take years for horseshoe crab populations to rebound and recover red knots. Harmful bait practices in South Carolina or New Jersey hurt red knots, which consequently negatively impacts the ecosystems in which they live in both South America and the Arctic.

Critical conservation

The red knot-horseshoe crab synchrony highlights the interconnectedness of wildlife and the difficulty in restoring species in a silo. No species is an island. Effective conservation requires broader attention to the wildlife crisis, not just a focus on federally listed species. That is the promise of the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act, which is making its way through Congress with bipartisan support. It provides funding for thousands of declining species that do not fall under the protection of the Endangered Species Act while restoring millions of acres of land.

If wildlife habitat is restored on a large scale, and both federally protected species, as well as unlisted, declining species, are supported, there will be better outcomes for all species. The synchronization of red knots and horseshoe crabs is a marvel of nature, and quite the sight to behold. Red knots can’t survive without horseshoe crabs, who can’t survive without worms and clams, who can’t survive without clean waters. Protecting red knot migration for future generations of birds and the people who love them requires care for all who call the Delaware Bay home.

Building Momentum: What’s Next for Beaver Conservation in Colorado