We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Why We Have Lawns

Many envision the ‘perfect’ American lawn as a lush, uniform green carpet that covers their outdoor space. But beneath this verdant facade lies a complex social history and significant environmental dilemma. The lawns that stretch across the United States, covering an astonishing 40 million acres—an area as expansive as Colorado—embody a tradition deeply rooted in cultural status but fraught with ecological consequences. These perfectly manicured landscapes, while picturesque, now consume around 9 billion gallons of water daily, introduce a myriad of toxins into our ecosystems, and offer scant refuge for the local wildlife that once thrived in these spaces.

Why then, do we even have lawns? This blog navigates the origins of lawn culture, from its aristocratic beginnings in Europe to its emblematic—and at time insidious—role in American suburbia. As we peel back the layers of tradition and confront the unsettling reasons our culture cherishes open green space to begin with, we invite you to reassess the allure of a lawn—to consider instead landscaping informed by a bright future, rather than a dark history.

Lawns as a Legacy of Luxury

Lush, manicured lawns are deeply rooted in the aristocratic traditions of Europe. Originating as a luxury of the European elite, the concept of the lawn as a landscape feature of manor houses was not merely an aesthetic choice, but a potent symbol of wealth and social standing.

In the grand landscapes of 17th and 18th-century European manor houses, expansive lawns served as the canvas on which the aristocracy could express their dominance over nature and display their economic might. These green expanses required an enormous amount of labor to maintain, far beyond what natural landscapes would demand. The aristocrats employed extensive staffs of gardeners or relied on grazing animals like sheep to keep their lawns at an aesthetically pleasing length. This reliance on manual labor or animal grazing underscored not only the lawns’ beauty but also the wealth and social status of the landowner—only those who could afford such exorbitant maintenance could possess a lawn.

The maintenance of these early lawns was a clear demarcation of social class. The need for a workforce to upkeep these green spaces created jobs, certainly, but also reinforced the division between the wealthy and the working classes. The landowners, with their sprawling lawns, stood in stark contrast to the common people, whose lands were utilitarian, used for growing crops and sustaining livestock.

The labor-intensive nature of lawn care in the aristocratic estates of Europe highlighted the social hierarchy, with the wealthy enjoying the leisure and beauty provided by their lawns, maintained by the labor of the lower classes. This division was a physical manifestation of the economic and social disparities of the time, with the lawn serving as a clear marker of aristocratic leisure supported by the toil of the working class.

American Adoption and Transformation of Lawns

Early American Lawns

When the United States emerged from the shadow of British colonial rule in 1776, the newly independent nation was eager to establish its own identity, both culturally and symbolically. This desire for distinction, combined with influences from abroad, set the stage for the introduction and adaptation of the European lawn in America.

It was during this period that contrasting perceptions between the Old World and the New World began to shape the American approach to lawns. Visitors from Europe often returned with tales that painted the American homestead as rudimentary and unsophisticated, frequently mentioning ‘yard birds’—a term used derisively to describe the chickens commonly kept in the modest dirt yards of post-Independence American homes. This portrayal did not sit well with the American elite, who were keen on showcasing the young nation’s success and sophistication.

Meanwhile, American diplomats and affluent individuals who had traveled to Europe returned with ‘lawn envy,’ having been impressed by the grand, manicured gardens and lawns of European aristocracy. Motivated by a combination of national pride and a desire to reflect the prosperity of America, the country’s wealthy set about importing this symbol of European refinement. Lawns began to appear on the landscapes of America’s grand homes, including none other than the White House itself.

Labor Requirements at Iconic Estates

Iconic estates like the White House and George Washington’s Mount Vernon Estate played a pivotal role in popularizing the lawn in American culture. Washington, along with other members of the American gentry, sought to emulate the aristocratic landscapes of Europe as a means of expressing their status and refinement.

However, the maintenance of these expansive lawns in America had a dark underbelly; it was heavily reliant on the labor of enslaved individuals. At Mount Vernon and similar estates, enslaved people were tasked with the grueling work of cutting the grass with only hand tools—a stark contrast to the pastoral tranquility the lawns were meant to project.

The adoption and transformation of the lawn in early America thus reflect a convergence of aesthetic desires, national identity formation, and the deeply ingrained inequalities of American society. As lawns became a symbol of the nation’s independence and emerging identity, they also became a canvas on which the contradictions of American life were starkly illustrated.

Democratization of Lawns

Into the 1860s, lawns remained out of reach to the common citizen. It was Frederick Law Olmsted, often celebrated as the “father of American landscape architecture,” who played an instrumental role in shaping the suburban landscape into one that valued open spaces and communal greenery. His designs for Central Park in New York City and the planned communities of Riverside, Illinois—one of the first planned suburbs in America— set a new standard for public and private spaces alike.

Olmsted envisioned the suburban landscape as a cohesive blend of natural beauty and structured design, where green spaces were accessible and enjoyed by all, not just the wealthy. This approach laid the groundwork for the American lawn as a shared communal asset, reflecting a strong, democratic nation rather than aristocratic exclusivity.

These ideas were further championed by Frank J. Scott in 1870, who saw the burgeoning American lawn as a canvas for expressing the nation’s democratic values distinctly from European traditions. In his extraordinarily popular book, The Art of Beautifying Suburban Home Grounds, Scott articulated a vision for the American lawn that emphasized openness and community over exclusion and division. He argued that “with our open-faced front lawns we declare our like-mindedness to our neighbors, and our distance from the English, who surround their yards with inhospitable brick wall.” Scott believed that the unenclosed front lawns of American homes symbolized a commitment to community and transparency, counter to the closed-off, exclusive gardens of Europe.

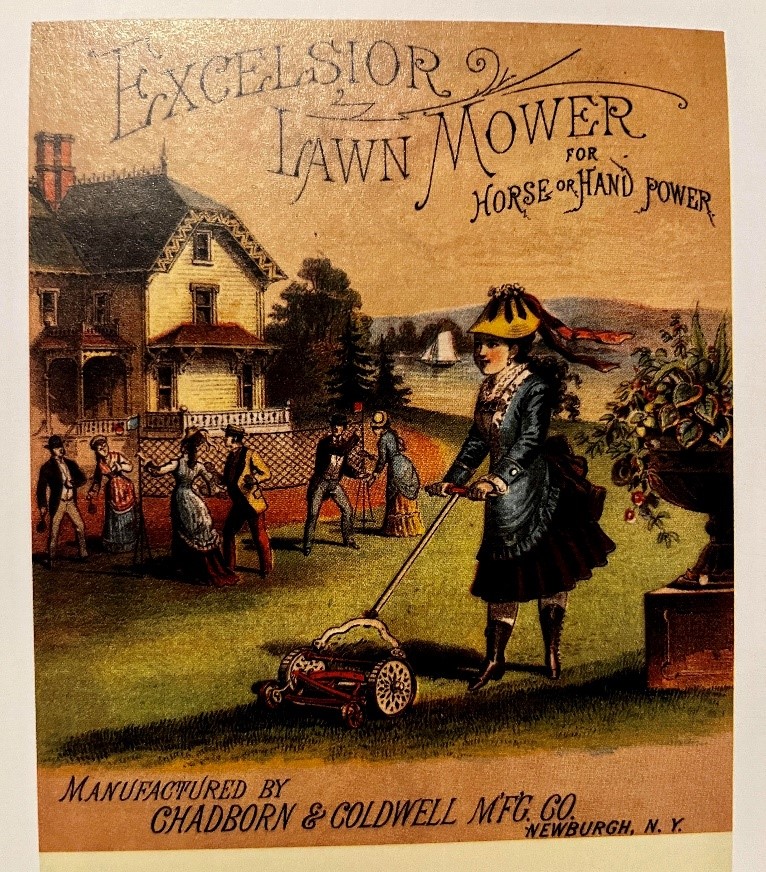

That same year, the introduction of Elwood McGuire’s push mower unlocked the possibility of realizing Scott’s vision of a democratized lawn. Before McGuire’s invention, maintaining a manicured lawn was labor-intensive and costly. But the push mower made lawn care more manageable and less time-consuming, allowing a broader segment of the American population to cultivate their own lawns.

The Dark Side of Green: Chemicals and the Perfect Lawn

From Warfare to Lawn Care

The transition from the battlefield to the backyard at the close of the first world war marked a dark and largely unacknowledged chapter in the history of American lawn care, deeply entwined with the activities of the Chemical Warfare Service (CWS), an agency initially established to develop and deploy chemical weapons for military use. As the guns fell silent and the world looked towards peace, the CWS faced a crisis of relevance. At the war’s end in 1918, the United States found itself producing four times as much poison gas as Germany. This surplus, and the very existence of the CWS, posed a question: what do we do with the knowledge and materials of war in a time of peace?

The First War on Wildlife

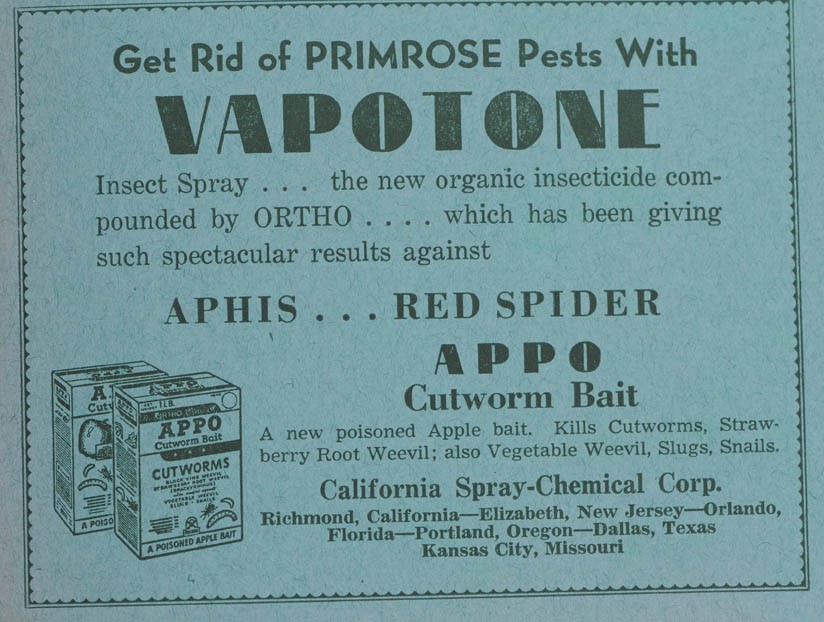

The CWS, slated for dissolution during peacetime, embarked on a campaign to repurpose its sinister expertise and resources for civilian applications. The rationale was straightforward—if these chemicals could be used to incapacitate or kill enemy soldiers, perhaps they could also be used to combat pests that threatened crops and gardens—and the chemists would not lose their jobs.

Rebranding itself as the ‘Chemical Peace Service,’ the agency began testing war gasses for use as pesticides, beginning with experiments using tear gas against boll weevils and rats in the 1920s. Some of the best-known war poisons, such as phosgene and chlorine gas, found their way into agriculture and water management—where they remain to this day.

This strategy was effective. In the eyes of the government, the CWS proved their worth during peacetime, securing the continuation and expansion of the CWS under the National Defense Act of 1920, which permanently cemented its place within the U.S. Army. And just in time; shortly after, use of chemical warfare would be banned by the Geneva Protocol.

The Second War on Wildlife

As World War II raged, the need for effective pest control became critical, especially in combat zones where insect-borne diseases were a significant threat to soldiers. The discovery of DDT (dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane) in 1939 offered a potent solution. DDT’s effectiveness against malaria and typhus-carrying insects was unparalleled, and its use during the war saved innumerable lives.

Following the war, the Chemical Corps, as it was now called, championed the domestic use of DDT. Along with burgeoning private pesticide companies, they promoted it as the ultimate tool for pest control, not just in agriculture but also in civilian settings including gardens and, notably, lawns.

The allure of an insect-free, perfectly manicured lawn was irresistible to many American homeowners—especially when chemical companies claimed these methods were not only safe, but ‘good for you.’ As a result, the application of DDT became widespread across the suburban landscapes of post-war America.

But the indiscriminate use of DDT had dire consequences, including the impending extinction of America’s national symbol, the bald eagle. Rachel Carson’s seminal work, “Silent Spring,” published in 1962, exposed the devastating environmental and health impacts of DDT, linking it to declining bird populations, poisoned wildlife, and even cancer in humans. Carson’s revelations lead to the eventual ban of DDT in the United States in 1972, though countless other harmful pesticides remain on the market.

The Modern American Lawn

The G.I. Bill and the Suburban Boom

The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly known as the G.I. Bill, was a monumental piece of legislation that provided a range of benefits for returning World War II veterans. Among these benefits, the provision of home loans dramatically increased homeownership in America, catalyzing the growth of the modern American suburbs. Homeownership rates surged from 44% in 1940 to 62% by 1960, fundamentally reshaping the American dream to include not just a home, but a patch of green lawn as well.

This post-war economic prosperity, coupled with policies that encouraged suburban living, led soldiers returning from the war to settle into the ‘American Dream.’ The introduction of the forty-hour work week in 1940, alongside the post-war economic boom, transformed lawn care from a chore into a hobby—and for many, a passion.

The Lawn as Civic Duty

In this era, the lawn expanded beyond its role as a personal pleasure or status symbol; it became a measure of civic responsibility. The perfect, uninterrupted green of suburban landscapes came to represent the ideal community—one where each homeowner contributed to the collective aesthetic and well-being of the neighborhood. This uniformity, while visually pleasing, also exerted a subtle pressure on individuals to conform to certain standards of lawn care, lest they disrupt the visual harmony of their community.

The lawn had become by now more than just a part of the home; it is a visible expression of adherence to community norms and values. The unspoken yet widely acknowledged expectation for well-kept lawns enforced a form of aesthetic conformity that extended beyond individual properties to define entire neighborhoods.

This pressure, worsened by the creation of Home Owner’s Associations (HOAs) in 1947, often overshadowed personal preference or creative expression, placing higher value on the collective image than on individuality. The perfectly maintained lawn became a symbol of control—a control not just over nature, but over personal expression.

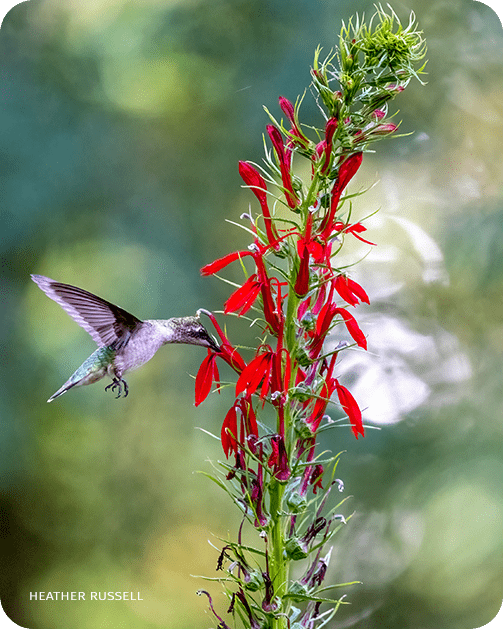

Rethinking the American Lawn

The cultural significance of lawns in America is unparalleled, with more than 40 million acres currently under cultivation. As we move forward, reevaluating the lawn and its place in American life is becoming crucial. The environmental costs, the social pressures to maintain a certain aesthetic, and the sinister historical roots of lawns invite us to rethink what we value in our landscapes. Could the modern American lawn evolve once more, this time towards sustainability, biodiversity, and a new understanding of what it means to live in harmony with the natural world around us?

Read the remaining blogs in this series:

- Part 2: Why We Shouldn’t Have Lawns

- Part 3: Grow Beyond No Mow May

- Part 4: Dangers of Lawn Chemicals: Impacts and Alternatives

Garden for Wildlife – Join the National Wildlife Federation’s Garden for Wildlife and Certified Wildlife Habitat® movement!