We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Protect Oak Flat: Understanding What’s at Stake

To know Oak Flat is to love Oak Flat.

Visitors love the scenic views of towering rocks, oak trees, and flowing water.

Locals love hosting family time and special events here, or just stopping by to pray for a while.

Environmentalists love the unique plants, wildlife and endangered species that make a home here.

Rock climbers love scaling the beautiful boulders steeped with deep red and orange hues.

And Indigenous peoples of the area love Oak Flat as a part of themselves.

Naelyn Pike, member of the San Carlos Apache Tribe, explains: “I look at Oak Flat as a major organ in the body, you can’t function without it…Without Oak Flat, we couldn’t be who we are.”

Oak Flat is Indigenous land

An hour east of Phoenix, Arizona, nestled in the Tonto National Forest, you will discover the wonder of Oak Flat, known as Chi’chil Biłdagoteel by the local Indigenous peoples. A place that holds immense historical, ecological, cultural, and spiritual significance.

Chi’chil Biłdagoteel is considered part of the ancestral homelands of the San Carlos Apache, Yavapai, Hopi, Zuni, and many other Tribes in the Southwest and is listed as a Traditional Cultural Property on the National Register for Historic Places. It’s a place where they can gather for cultural ceremonies, such as young girls’ coming of age, sweat lodges, and prayer circles; collect acorns and medicinal plants; and honor fallen ancestors who were buried here.

To Indigenous communities, Chi’chil Biłdagoteel is synonymous with a church or temple. It is where they practice their religion and spend valuable time with their families and community. It is where they go to feed their minds, bodies, and souls.

Mining in Oak Flat

Despite the invaluable resources and values of Oak Flat, a foreign mining company wants to change this sacred place forever.

Resolution Copper, a joint venture of two Australian-based mining companies, intends to mine one of North America’s largest copper ore deposits at Oak Flat. They are motivated by the profitability of copper, a fully recyclable metal that’s essential for clean energy technologies, mobile devices, and medical equipment. The owners of Resolution Copper, BHP and Rio Tinto, have a documented record of destroying Indigenous sacred sites around the world.

Oak Flat, which was specifically withdrawn from mining by President Eisenhower in 1955, should have never been available to a mining company. However, in 2014, Senators John McCain and Jeff Flake added a last-minute rider (Sec. 3003) to the “must-pass” National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), mandating the transfer of Oak Flat to Resolution Copper within 60 days of the publication of a Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) for the mine project.

“It was a sneaky, underhanded thing that was done at the last minute in a smoke-filled room with no public comment,” says Curt Shannon, a long-time rock climber who has frequently traveled to D.C. to advocate on behalf of saving Oak Flat.

With just five days left before leaving office, the Trump Administration published a rushed FEIS to start the 60-day transfer clock. Fortunately, the FEIS was rescinded in March 2021 by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) under the Biden Administration to “conduct a thorough review” and “to fully understand concerns raised by Tribes and the public and the project’s impacts to these important resources and ensure the agency’s compliance with federal law.”

But an updated version could be published at any moment. Advocates of Oak Flat have been working tirelessly to ensure that the FEIS accurately states the potentially devastating impacts. To this day, they have successfully delayed the land swap process, advocated to protect Tribal religious freedoms, and demanded a more thorough investigation.

Mine opponents consider Resolution Copper’s proposed “block cave mining” method as the first red flag of many.

Even the rescinded FEIS projects that this method proposes would create a 1.8-mile-wide and 1,000-foot-deep crater, effectively destroying the sacred land forever. That’s only an estimation—the actual damage could be much greater. Plants at the site, including medicinal varieties like sage, bear root, willow, greasewood, as well as the abundant Emory oak, would be eradicated. With no habitat and vegetation, wildlife—such as deer, squirrels, birds, mountain lions and more—will be forced to relocate.

A hydrology report by the Bureau of Land Management additionally concluded that precious water resources will be at serious risk.

“There are two aquifers that sit below this mine. This block caving technique is going to destroy, contaminate, and pollute those two important aquifers that feed the town of Superior and the large population just 30 miles west of us,” explains Henry Muñoz, a fifth generation former miner and resident of Superior, the neighboring town to Oak Flat. As a mining expert and advocate, he translates lengthy environmental impact studies for communities and policymakers to understand what is at stake.

Muñoz cites that in addition to contaminating water, the mine would significantly deplete water supplies. Using the rescinded FEIS projections, a study estimated that the operation would require over 250 billion gallons of water—enough to sustain a city of 140,000 people for 40 years. For a state that is already facing the drastic effects of climate change, unprecedented drought, and cutbacks to use of the Colorado River, the misappropriation of water would be devastating to local communities and the entire region.

Long-lasting harms of mining

Once the copper is extracted from the ore, the next concern are the tailings, or toxic waste.

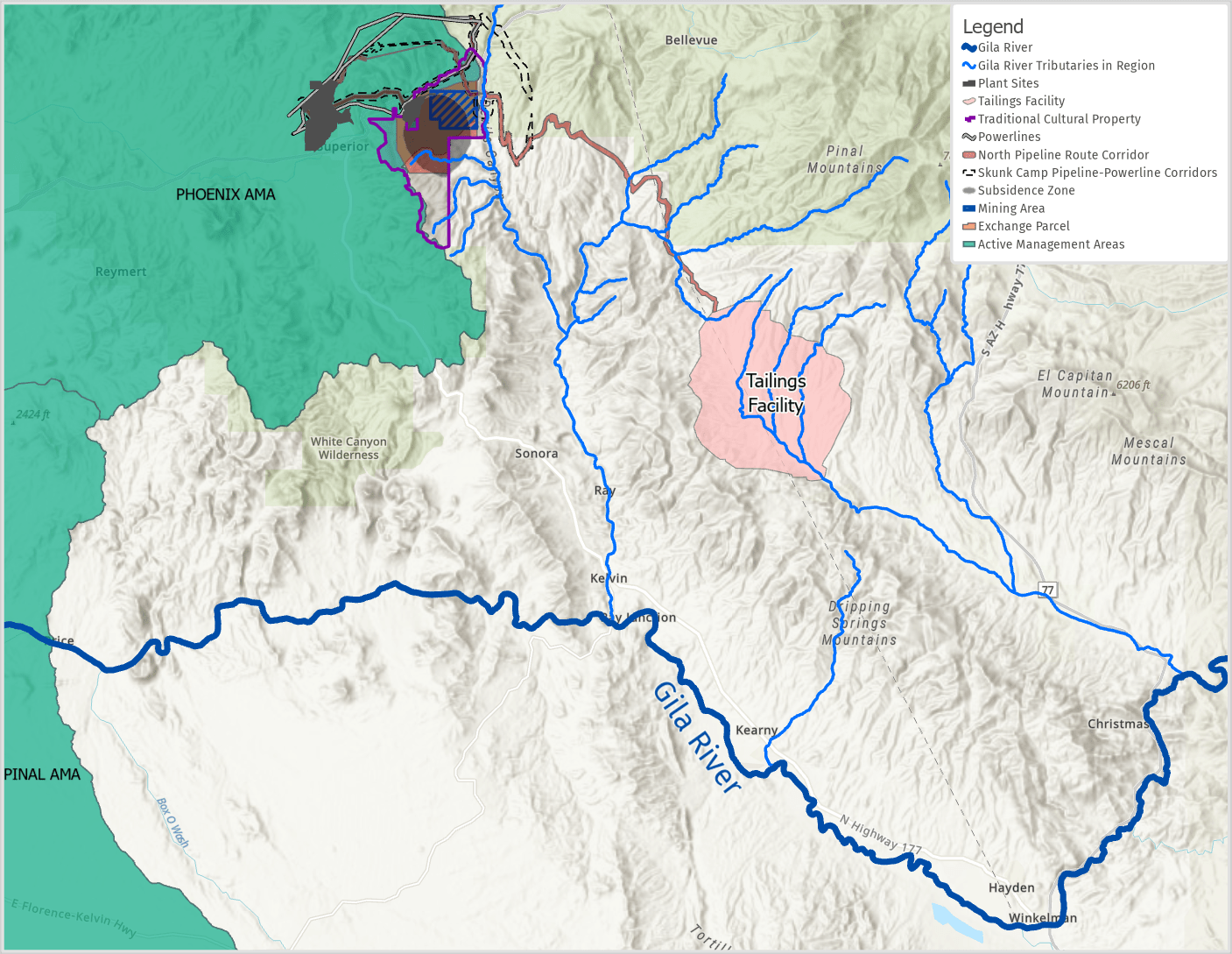

The FEIS determined that the mine would generate 1.37 billion tons of toxic tailings. This waste would be mixed with water and transported through a pipe 17 miles south of the subsidence zone (or crater). Covering nearly 4,000 acres in a facility of over 8,600 acres, the tailings dam would be one of the largest facilities of its kind in the world. To prevent toxic dust dispersal and leakage, the tailings would need to be soaked with water and managed in perpetuity.

If the pipeline or dam were to rupture and fail, it could result in catastrophic harm to people, property, wildlife, land, and water. Muñoz also warns: “If we had a storm of high magnitude hit that area, those tailings would flow into the Gila River…Five towns along the river would be immediately impacted by contamination.”

In the wake of the proposed mine, human health impacts are yet another serious threat.

In Superior and the surrounding mining communities, collectively known as the “Copper Triangle”, environmental contamination has resulted in numerous health concerns. Muñoz references community experiences and the FEIS, noting that cancers and respiratory illnesses are especially prevalent, attributed to high levels of copper and arsenic in the water, and air pollution from smelters. Community science efforts, such as the University of Arizona’s Gardenroots Project, empower Superior residents to understand the effects of contamination and improve the environmental quality of their neighborhoods.

Other components of holistic health are mental and spiritual. If the proposed mine goes through, it would take away Indigenous communities’ ability to practice their culture and religion—their first amendment right. Pike explains that severing one’s sacred connection to the land leads to social illnesses in her community, such as high rates of suicide, substance abuse, domestic violence, and diabetes.

“Without the land, we can’t really be who we are as human beings… Without that interconnectedness, we can’t speak our language, we can’t practice our culture, our traditional ways of life. And then in the end, we become like zombies, assimilated, an empty carcass.”

Naelyn Pike, Chiricahua Apache

Despite the overwhelming environmental, health, and cultural impacts, Resolution Copper claims that they will mine “safely and responsibly” and provide “long-term economic benefits” to local Arizonans.

The company boasts that the mine will bring 3,700 jobs and billions of dollars to Arizona’s economy. Even if that were true, the project will only provide these benefits during the estimated 40-year life of the mine. And since the copper is expected to be shipped to China for refinement, Americans will likely have to buy back the product that was mined domestically. If the operation persists, the future is dim.

Superior will no longer be able to diversify their economy and attract tourism. State tourism is highly sustainable and generates about three times as much revenue as the state’s mining industry does. A huge crater, depleted and contaminated water supply, and the threat of toxic tailings will be the lasting mark. The benefits do not justify the devastation.

“We support the green energy transition. But it doesn’t make sense to turn the environment ‘brown’—destroy or pollute it—to go ‘green’” explains Daniela Zavala, Director of Communications at Hispanics Enjoying Camping, Hunting and the Outdoors (HECHO). HECHO’s mission is to advocate for the protection of public lands and waters by amplifying the voices of Hispanic leaders in the community, such as Muñoz and others. HECHO is part of a large coalition of organizations who have banded together to save Oak Flat from environmental destruction.

Read part two of this series here.

Building Momentum: What’s Next for Beaver Conservation in Colorado