We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

How the Great Northwoods Have Shaped Generations of Residents

In the late 1970s, Linda and Victor, a young couple born and raised in the Detroit suburbs, lost interest in city life. They yearned for the tranquility that accompanies rural living, and wanted to raise their small children—Lisa, Ryan, Lee, and Christopher—away from the dangers of the metropolitan area. So, they found a property for sale in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and never looked back.

It’s been 46 years since, and the couple hasn’t moved. Linda cited the peace as what she loves most about their home, and Victor agreed, adding, “When [people have come] to visit over the years, they’ll say it’s quiet here. . . . I says, ‘That’s what I like.’ . . . . It’s one of the few places you can live where there isn’t continuous noise.”

That’s because swaths of forest surround their homes, tamping down noise pollution and creating an exhilarating source of entertainment for their children. Over the years, the boys built tree forts, ziplines from rope and horseshoes, and bows, while challenging one another to climb towering maples, trapping one another in homemade snares, and hunting, among other activities.

The woods that raised this family are part of the famed Great Northwoods—more than 60 million acres of pure, intact forests spanning Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota.

Unfortunately, as time goes on, things can’t remain the same. For the twin sons, Ryan and Lee, that meant moving on from the Upper Peninsula.

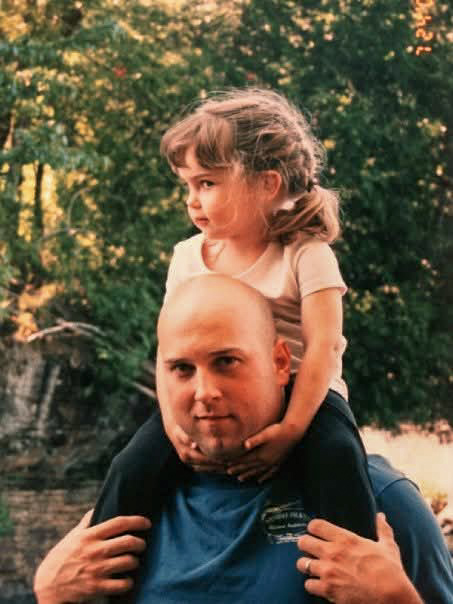

Today, Ryan lives in Utah and Lee in Texas. But while the twins no longer live in Michigan, that doesn’t mean they abandoned their love for the woods. To this day, the twins regularly meet in the middle to camp, fish, and/or hunt. And when they can’t do it with each other, they’ll do it alone; the need to be in the woods is embedded deep within them.

“For me, whenever I feel stressed or [anxious] or [any] bad energy I need to get rid of, I can go walk in the forests, up in the mountains, or the forests at [my dad’s], wherever the forest is,” says Ryan. “Maybe it’s just the sound of the wind going through the trees, or just looking up [at the canopy]. Maybe it takes me back to my childhood when life was simple. But that’s what I feel. It just blows all the stress away.”

Ryan isn’t alone in this, as immersing yourself in the woods can provide many health benefits, ranging from reduced blood pressure to boosted immunity to improved well-being. For a man with chronic heart problems, this has helped ease the pressure on his heart, which stems from the woes of day-to-day life.

But the impact of the woods doesn’t merely stop at the second generation.

Although I didn’t live in the Northwoods nearly as long as my father Ryan, those forests still sit with me. I now live in North Carolina, and regularly reminisce about the awe-striking trees and local wildlife that visited my childhood home. It’s those memories, combined with my desire to protect threatened ecosystems like the Northwoods, that inspired me to work in forest communications.

I didn’t live in Michigan for more than 10 years, but it’s those 10 years that shaped who I am today. The woods, the animals, the simplicity of it all… It’s, without a doubt, the reason I care so deeply about the environment, and have gone as far to pursue a career that protects and restores forests for wildlife and people alike.

There isn’t a single member of my family who can envision growing up without those forests, given how integral they were in shaping our lives. From my grandparents Linda and Victor to myself, our story showcases the multi-faceted impact of these woods. On one hand, it’s shaped coping mechanisms for stress and anxiety; on the other hand, it’s influenced a career. It goes to show how important this ecosystem is not only for the wildlife but for the residents who call it home.

There’s nothing truly comparable to the Northwoods, and if we don’t protect it, we’ll lose it for good.

To get involved, visit our website.

Building Momentum: What’s Next for Beaver Conservation in Colorado