We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Witnessing Wildlife and Climate Out of Sync

Like anyone who enjoys photographing nature, my first impulse when temperatures hit 70 degrees F in February was to grab my camera and head outside. This was unseasonably warm for Virginia, so I thought I might catch some wildlife in action. In fact, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration recently announced that February 2017 was our second warmest and this winter was the sixth warmest on record, with the average temperature in the lower 48 states being 35.9 degrees F, or 3.7 degrees above the 20th-century average. That is quite a jump.

While I got some nice shots of some plants budding, I was feeling a bit guilty about enjoying this reprieve from winter’s chill. After all, the rise in global temperatures is causing volatile weather that’s wreaking havoc on humans and wildlife. In January, parts of southern California that had suffered five years of severe drought suddenly drowned in mudslides after days of severe rain. In February, Massachusetts experienced its first tornado. National Wildlife Federation Naturalist David Mizejewski saw bats flying overhead in February when they should have been hibernating, and this month, my flowers are covered in snow. Mizejewski says what many of us are thinking: “Wow, this shouldn’t be happening.”

So as our world continues to warm, what will this mean for wildlife? Even some of the species in our own neighborhoods may no longer be a common sight. In a recent paper in PLOS, University of Arizona researcher John Wiens reports that populations of 450 plants and animals worldwide have been “unable to undergo niche shifts that are fast enough” to adapt to changing temperatures and consequently have gone “locally extinct from climate change.”

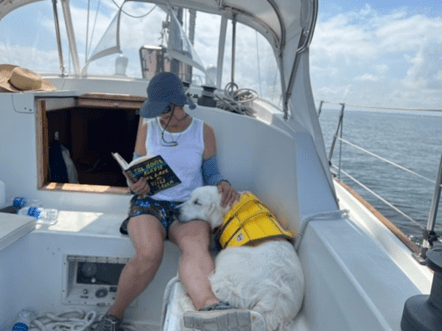

While most photographers may not be thinking about their subjects disappearing before their eyes, the conservation value of photography should not be underestimated. The following photos—all entries to National Wildlife magazine’s annual photo contest—show just a handful of the species struggling to adapt to an altered climate. This year’s contest will soon close, so whether you are on an expedition abroad or in your own backyard, take your camera and send in your images. You just may help document a rapidly changing world.

Increased Parasites

Shorter winters have allowed parasites such as winter ticks to thrive. Moose are being covered in hundreds of thousands of ticks, which can weaken and kill even adults. This has severely depleted moose populations in Minnesota, New Hampshire and Maine.

Melting Snow Blankets

Warmer temperatures do not necessarily mean that all animals will be warmer in winter. Snow can serve as an insulating blanket for small, burrowing animals such as voles and mice, protecting them not only from bitter cold but also from predators such as the least weasel. In addition, warm air holds more moisture, so as temperatures climb, once–dry and fluffy snow becomes wetter, denser and colder. Snow cover has declined and is melting earlier in the year. Some scientists predict that the number of days with snow will decrease up to 80 percent by the end of the 21st century.

Mismatched Camouflage

Shortening the length of time that snow is on the ground can be deadly for animals such as the snowshoe hare, which changes its fur color from brown in summer to white in winter to blend in with its environment. In a snow-free landscape, white hares are easy targets for predators. Last year, biologists at North Carolina State University reported in Ecology Letters that when snowfall comes late or leaves early, hares suffer a 7 percent decline in their weekly survival rate due to increased predation.

Peaked Pikas?

In the Great Basin and Sierra Nevada regions, pikas live in talus (loose rock) on cool, moist mountain slopes that range from 7,000 to 12,000 feet above sea level. To survive in cold climates, pikas have thick, dense fur and high resting body temperatures of about 104°F. U.S. Geological Survey Researcher Erik Beever has found that pika populations have vanished from hotter and drier parts of their historical range at lower elevations across the Great Basin and in California, and that between 1999 and 2008, pika populations across the Great Basin moved upslope by an average of 476 feet. As Beever says, “That’s smokin’ fast.” However, he and others are also finding that these tough little critters are thriving in pockets of cooler habitat —refuges that may help pikas survive a changing climate.

Starvation

Many bats hibernate in winter, living off the fat they stored in warmer months from devouring millions of insects each year, including mosquitoes. If they are disturbed from their slumber before bugs are available, they will drain these fat reserves and potentially starve or be so depleted they cannot successfully breed or feed their pups. Many bat species are already dying in the millions from the fungal disease white-nose syndrome, so any additional stress could further deplete bat populations.

Mixed Signals

Many amphibians, including the spotted salamander, also hibernate, and winters that are too warm and dry could be deadly for them. A winter with low precipitation may mean the vernal pools they have returned to year after year to breed may not yet have formed. Or, if they do reach these pools and the water suddenly refreezes, the animals and any eggs they laid could perish. This year, salamanders and wood frogs were already on the move by February 25 in New York’s Hudson River Valley, where since 2009 more than 300 volunteers have helped some 8,500 amphibians cross the road, recording the species they observe. Laura Heady, who leads this citizen science program for the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, says some volunteers this year already have heard wood frogs singing and seen eggs laid in ponds. This is the earliest the amphibians have started their migration since the program began, says Heady, but then as “weather is becoming more and more dynamic with climate change, we all might have to recognize that this is the new normal.”

A Changing Backyard Scene

What you see at your bird feeder today may be different in years to come. University of Wisconsin–Madison researchers examined tens of thousands of citizen-science reports from Project FeederWatch, run by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Bird Studies Canada. Winter backyard bird counts in the eastern half of the United States showed that 38 common bird species—including blue jays, eastern bluebirds (above), American goldfinches, Carolina wrens, chipping and song sparrows and purple finches— have shifted their range, moving approximately 96 miles north from 1990 to 2011.

Frozen Flowers

The sudden onset of cold can damage plants, especially when several springlike days in winter are followed by a sharp cold snap. This can freeze water inside and outside a plant’s cells, puncturing and killing them. This is particularly hard on new growth or fragile blossoms, the nectar of which pollinators such as bees, wasps and bats depend on for food. Bumble bees may be particularly in trouble. Unlike other species trying to adapt to a changing climate, most bumble bee species have not shifted their ranges northward as temperatures rise, and the insects are disappearing from southern portions of their ranges. This could be bad news for us as well, as some three-quarters of flowering plants, including many of the crops we eat, are fertilized by pollinators.

Your photos could help wildlife. Submit your entries to the 46th annual National Wildlife Photo Contest before time runs out!

ENTER YOUR PHOTOS