We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Good PR for Beavers

A pilot project in western Montana shows how people and beavers can coexist

Beavers have a rich and interesting history in America. Trapped to near extinction in the 1800s, beavers are returning to their old haunts, and with them come benefits that more and more people are recognizing. Beaver dams hold water and recharge aquifers. They slow down water in small streams, which in turn reduces erosion, improves water quality, and helps expand riparian areas. Their ponds create diverse habitat to support fish, birds, amphibians, and mammals. As Montana and the West face a hotter and drier future, more beavers on our landscapes may be just what we need.

But beavers have a bad reputation for creating some problems for humans. Beavers mean trouble if they damage or cut down valuable landscape trees. If they dam culverts the resulting impounded waters can wash out a road, and if they block irrigation ditches the water can flood a farmer’s fields. What happens next is usually not good for the beavers, but trapping and killing nuisance beavers seldom provides permanent nor useful solutions. That’s why we believe there’s a better way.

The National Wildlife Federation and its partners, the Clark Fork Coalition and Defenders of Wildlife, recently launched a 6-month pilot project to test and demonstrate techniques that allow beavers to stay on the landscape while simultaneously solving the problems they can cause.

Sarah Bates, the Federation’s Senior Director for Western Water, described the goals of the project as providing beavers with some public relations help. “We want to change the perception that beavers are nothing but a nuisance by addressing people’s real concerns with the impacts of their natural behavior,” she said. “With this project, we’re testing some devices and practices that have worked in other parts of the country to help us coexist with beavers–which, in the long run, often end up being less expensive and more efficient than trapping and other lethal methods of control.”

The pilot project is run by Elissa Chott. As the new Beaver Technician at the Clark Fork Coalition, she brings years of experience addressing conflicts between bears and people. Elissa’s job is to find places where beavers are causing problems within the Clark Fork River Basin in western Montana. She works with landowners, county road crews, state parks and wildlife managers, and conservation partners to show how beaver damage can be minimized by installing a few simple devices.

Problems and Solutions

Starting with one of the most basic nuisances that beavers are known for, the project aims to address the problem of beavers chewing through trees that provide a host of benefits to the land and communities. One solution is to wrap the trees with cylinders of heavy wire that beavers can’t chew through. This protects the trees and beavers turn to other vegetation for their food and building supplies.

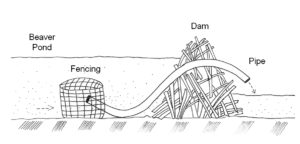

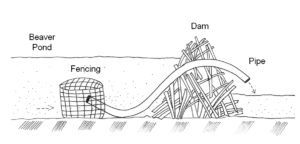

Another common problem occurs when beavers dam a culvert, and the rising water floods or washes out a road. A solution to this is constructing a fence that prevents beavers from accessing the culvert; one version of this approach bears the trademarked name “Beaver Deceiver.” Beavers try to build dams wherever they sense running water, but if they can be kept far away from that stimulus, they don’t bother. A 40-50 foot-long fence constructed in front of a culvert’s upstream opening does the trick. The fence is shaped like a trapezoid, so even if beavers try to dam the fence near the culvert, the shape of the fence forces them further and further away from the sound of the water, until eventually they give up.

Beyond in-stream structures, researchers from Utah have been experimenting with simple white sheets or flags erected at a culvert to deter beavers. One enterprising Gallatin Valley farm family has even used an inflatable “scary clown” at a bridge where their otherwise-welcome beavers were blocking water and flooding their road. (“When the Beavers Met Bozo” is an amusing photo story, if not a definitive guide to controlling beaver activity.)

In addition to causing problems at manmade “pinch points” such as culverts and bridges, beaver ponds can overflow into farm fields or flood roads and other developed areas. In these cases, a device called a pond leveler can help. Pond levelers act like the overflow drain in a sink. A flexible pipe, submerged in the beaver pond drains the backed-up water to a desired height. The water is released on the downstream side of the beaver dam. The pipe’s intake is surrounded by a cylinder of wire fencing that keeps the beavers too far away to hear the water flowing into it, so they don’t try to fix the “leak.”

Pioneering beaver conflict specialist Mike Callahan, based in Massachusetts, has designed and installed hundreds of these devices, and his monitoring data show that the long-term success of preventing beaver damage is over 90 percent. In a campaign to support these methods all around the country, Mike founded the nonprofit Beaver Institute, which offers online training and live mentoring for a growing “Beaver Corps.”

Here in Montana, Elissa Chott finds that, “Most landowners I’ve talked to are willing to live with beavers as long as they don’t cause a lot of damage or flooding.” Perhaps the chances are good that beavers will also become more accepted as ways to coexist are better understood.

Learn more about the Montana Beaver Conflict Resolution Pilot Project here, and learn more about beaver management at Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks’ Living With Beavers website and at the Miistakis Institute’s Landowner Resources website.