We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

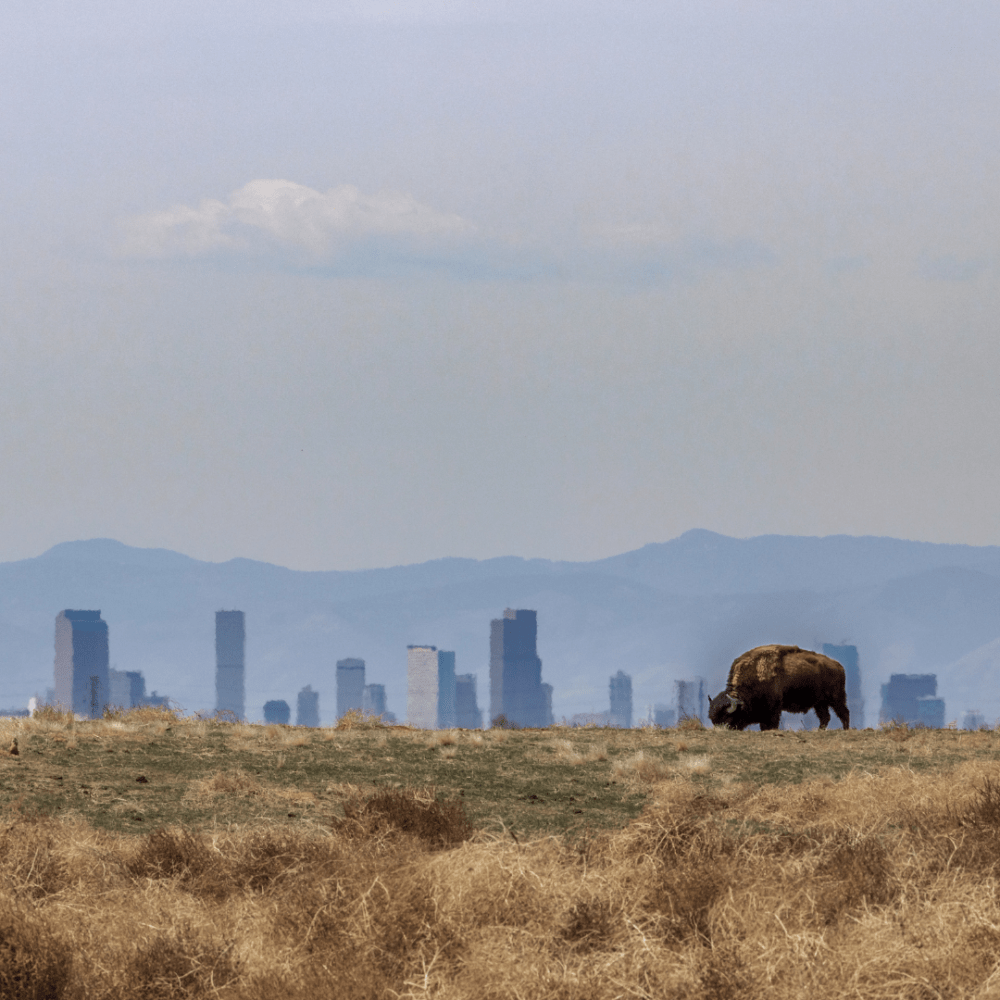

The Future of Conservation

Many elders often share that their biggest hope for the future lies in youth.

As a young woman and dedicated environmentalist, I’ve learned to internalize that responsibility. My generation has inherited a planet that is suffering—one that faces pervasive pollution, exploitation of precious resources, and the devastating impacts of climate change. If we wish to sustain our home for generations to come, we have no choice but to embody hope for the future.

While elders are placing their hope in youth, where do we find ours?

Finding hope in our roots

To answer this question for myself, I must look to my roots. I am a descendant of Filipinos, a people who embody great resilience and community care. Before colonizers touched down on our islands, our Indigenous culture thrived. With limited resources and whole communities to feed, my ancestors were creative, tenacious, natural-born environmentalists. I come from a long line of skilled farmers, fishers, and basket weavers, but my family no longer remembers their stories.

Although centuries of colonization have erased much of our Indigenous culture, I’m committed to unearthing their ways of life and discovering my own indigeneity. My hope comes from my ancestors who instilled their strength in me, and guide my conservation efforts.

I acknowledge that I live and work on stolen land, specifically Tongva land (Los Angeles, CA). As a good steward, my duty is to learn from the Indigenous peoples of the land I’m on who carry thousands of years of Intergenerational Knowledge.

No monopoly on knowledge

I earned my degree in Environmental Studies from a Western institution but found the education somewhat incomplete. I’ve always been fascinated by Indigenous Knowledge, in ways that Western science cannot explain. There’s a spiritual dimension to our connection with nature that is often overlooked in the classroom. In Native American culture and nature-based spirituality, I see my values reflected—and the deeper I dig into Indigenous cultures, the more I recognize the common threads that connect us all.

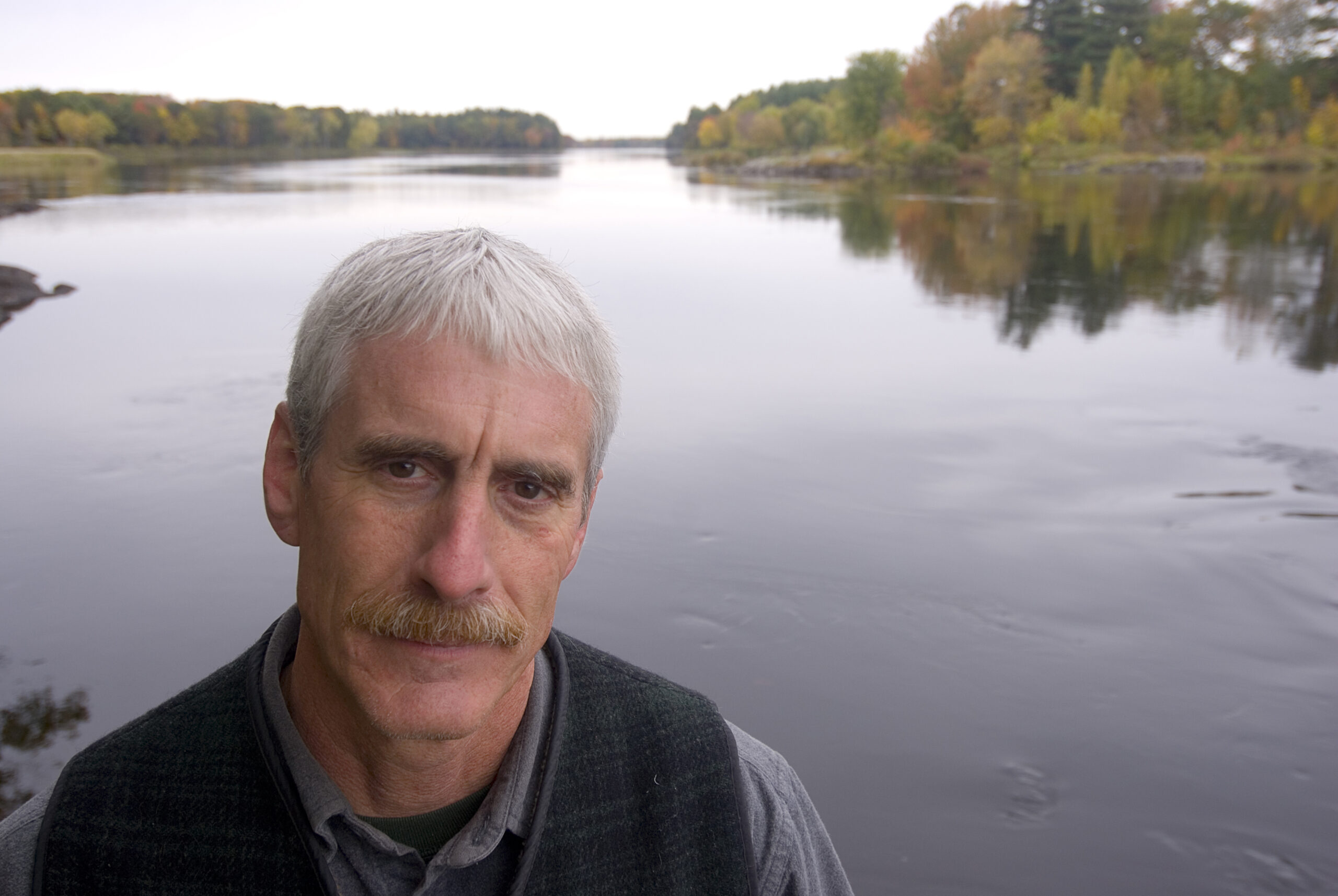

I recently had a conversation with a Tribal elder named John Banks who offered insight on my musings. John is a citizen of the Penobscot Indian Nation in Maine and member of the newly formed Tribal Advisory Council for the National Wildlife Federation (NWF). He demonstrates the perspective of Etuaptmumk, or “Two-Eyed Seeing”—having been raised in the values and culture of his Tribe and educated in Western forestry science at the University of Maine.

He told me a story about the time a Tribal elder, named Harry Francis, explained to him the five species of ash trees in Maine. John had freshly graduated from college at the time, and replied that there were, in fact, only three species of ash trees in Maine:

“I’ll never forget that he said, ‘John, what the heck are they teaching you over there at that University?’”

For John, this interaction opened his eyes to the limitations of his own Western education:

“Harry didn’t have to learn anything by going to college and listening to a professor’s lecture or reading a textbook. His base of knowledge came from the direct interaction with the resources and learning from his elders and teachers.

That whole body of knowledge has been suppressed so much. Many universities and academies don’t recognize the value of thousands of years of direct knowledge.”

The lack of Traditional Knowledge in John’s forestry education was also a primary reason for two of his friends dropping out of college. The Western teachings simply did not resonate with them as Tribal youth. This and several other factors contribute to a trend of higher dropout rates among Native Americans than other ethnic groups in the United States.

Western science is largely focused on empirical evidence, objectivity, and the scientific method. But implementing only one school of thought is detrimental to achieving shared conservation goals. Traditional Knowledge offers a holistic perspective rooted in lived experiences, cultural heritage, and long-term thinking. In the Indigenous worldview, everything is purposefully interconnected. Despite their differences, these perspectives can be complimentary when combined together.

Pathways to meaningful education

The relationship between Western science and Indigenous wisdom is at the heart of initiatives like the Wabanaki Youth in Science Program (WaYS). Co-founded by John and others, the program empowers Native youth in Maine by merging these worldviews, creating an enriching educational experience. To explore this further, John introduced me to his former colleagues, Darren Ranco and tish carr, who now lead WaYS.

“My job is to create pathways for the educational success of our Native students who go on to have a positive effect on our communities, through healing and conservation work.”

Darren Ranco, Chair of Native American Programs at University of Maine and a founding member and ex-officio member of the WaYS Board

WaYS is a grassroots, community-based program focused on building long-term relationships with Tribal youth in Maine and supporting their educational and career paths. WaYS offers hands-on educational and conservation opportunities through camps, internships, afterschool programs, 1:1 mentorship, and more.

They pair Cultural Knowledge Sharers with Western science professionals to co-teach students in the way of Two-Eyed Seeing. tish carr, the Executive Director of WaYS, proudly shared that many WaYS graduates have earned their degrees in higher education, attained their dream jobs, and often come back as role models for current participants.

Empowering the youth opens pathways to meaningful careers in conservation. It reminds me of the start to my own journey, when I found my calling at age 15 in an AP Environmental Sciences class (shoutout to Ms. Paniagua!). It’s humbling to remember that without good teachers and role models, we may never end up in the fields where we have the most to offer.

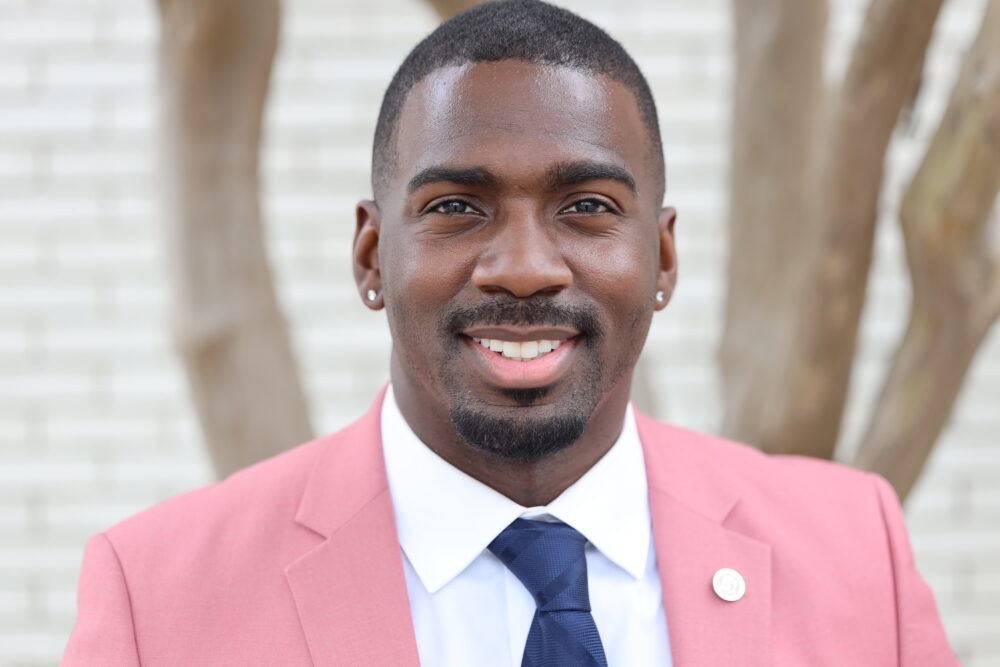

Someone who’s considered a role model among the Indigenous youth communities of Santa Fe, New Mexico is Andrew Black, Public Lands Field Director at NWF. Born and raised in Santa Fe, Andrew has a deep reverence for and connection to the local Pueblos and Native American cultures. He’s passionate about collaborating with Tribal youth and elders to advance traditional practices like fly tying, fly casting, and learning the language of the outdoors.

Over the years, he has developed strong bonds with Tribal youth, some of whom have gone to college and returned to teach the next generations. At the core of his work is a commitment to providing for his daughter and future generations.

“The seeds that we’re sowing today, we may never see the fruits of. But we have to trust that the fruits will be there for the next generations to come. It’s our job to do that work as stewards of creation,” Andrew shared.

Andrew introduced me to his colleague, Rosemary Reano, who co-leads youth programs with him, such as the Kewa TRUTH (Teens Reaching Unity Through Harmony) Youth Council. As a young mother from the Santo Domingo and San Felipe Pueblos, she recognizes the utmost importance of empowering Tribal youth.

“Indigenous youth are vital to preserving and advancing Traditional Ecological Knowledge. Their ability to blend traditional practices with innovative solutions position them as powerful agents of change,” said Rosemary Reano.

Transmitting conservation knowledge

The conversations I had over the past few weeks helped me understand the key elements of successful Intergenerational Knowledge Transmission. It comes down to the building blocks of humility, trust, and reciprocity.

Humility is the reminder that Western science is not the only way, and un-learning colonized beliefs is essential to understanding and accessing the true value of Indigenous wisdom. Contrary to some Western beliefs, humans are active agents of conservation, and intervention (in a good way) is often necessary.

Trust is built through authentic, long-term relationships. Meeting people where they’re at and connecting over shared values are key. A solid foundation of trust enables a diverse community to embrace and embody the change they wish to see.

Reciprocity is how the cycle of leadership continues. Reciprocity ensures that when the youth grow up, they return to their roots and offer new teachings to raise the next generation. This exchange is vital to sustaining cultural and environmental stewardship.

Through my conversations with John, Darren, tish, Andrew, and Rosemary, I’ve solidified a belief that my ancestors have always known: the past, present, and future of conservation is Indigenous.

As I advance in my career, I’m committed to honoring and advocating for Indigenous-led conservation. This work is about restoring harmony between people and the natural world, a harmony that Indigenous communities have upheld for millennia. Through this lens, I see my role as a conduit of the teachings that have always been there, ready to guide us toward a more hopeful future.

Continue learning about the modern application of Indigenous wisdom:

- Etuaptmumk: Two-Eyed Seeing | Rebecca Thomas (TEDx Talks)

- Robin Kimmerer – Mishkos Kenomagwen: The Teachings of Grass (Bioneers)

- Can Indigenous knowledge and Western science work together? New center bets yes (Science Insider)

- Indigenous Knowledge, western science braided into recommendations for land managers (Oregon State University)

- Indigenous Knowledge (The White House)