We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

The Life of a Solitary Bee

Bee species’ behavior has fascinated humans for eternity. Throughout the world, we watch them buzzing from flower to flower, collecting pollen. From classical songs to company logos and home décor, we have honored their existence. It’s easy for many of us as casual observers to believe that we understand them, but the bee world is more fascinating than we realize.

There are up to 4,000 native bee species in the United States, according to the U.S. Geological Society. Yet, the average person is likely more familiar with the (non-native) honeybee who goes back to the hive buzzing with life with a queen, her workers, and her mates. Our general understanding of bees is not the full truth. During a recent webinar from our What’s Buzzing in Texas? webinar series, Dr. Jessica Beckham from the University of Texas, San Antonio, explains that hive-oriented or “social” bees like honey bees or bumblebees are the exception in the bee world. Most bee species lead solitary lives.

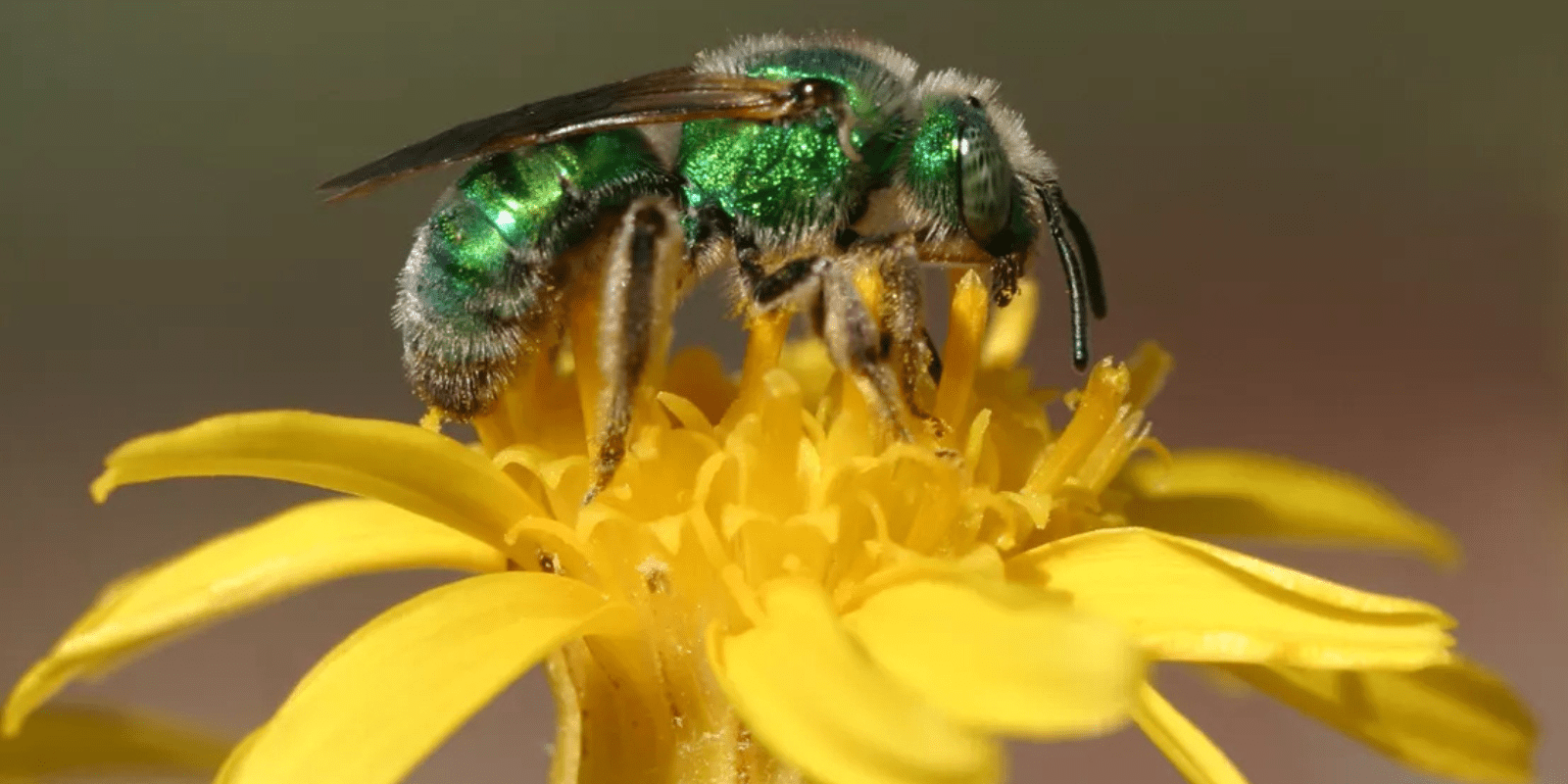

Solitary bees make up about 98% of the native bee species in the United States, according to the University of Minnesota Bee Lab website. With thousands of species, it’s not surprising that these solitary bees come in a variety of sizes, shapes, and colors. They exhibit a variety of different behaviors, too. For all the differences, the one trait all these species have in common is that they live alone.

The Independent Female

Solitary species like carpenter bees, mason bees and some sweat bees, carry on their lives in a very different manner from their social counterparts. The adult female lives independently without any shared work duties with others of her species. She alone carries out all the duties usually delegated to different members in a hive setting.

Depending on the species, the solitary female may create her nest underground, in the hollows of plants, in rock crevices, or with a plastic-like material she creates. Dr. Beckham notes that solitary females are not as defensive of their abodes and will instead fly-off if something happens. As a result, there are some solitary female species that will take over the nests of other bee species to lay their larvae rather than create a nest of their own.

The Solitary Male

All solitary bees live for about a year with much of that time spent in the early development stages from larva to pupa. Their adult lives last only three to eight weeks. During this stage of life, solitary male bees only have one function—to mate.

Because of the lack of a hive or communal habitat, the solitary male bee will sleep in flowers during the night while it competes for mating with nearby females. Dr. Beckham observes solitary males return to her garden every night to sleep among her flowers.

How to Help the Solitary Bee

While not discussed as much, solitary bee populations are declining. Considering that solitary species are the majority of bee species in the United States, there will be dire impacts if we do not do more to protect these bees. While bee conservation should be addressed on a massive scale, Professor Beckham listed a few ways you can help solitary bees in your yard:

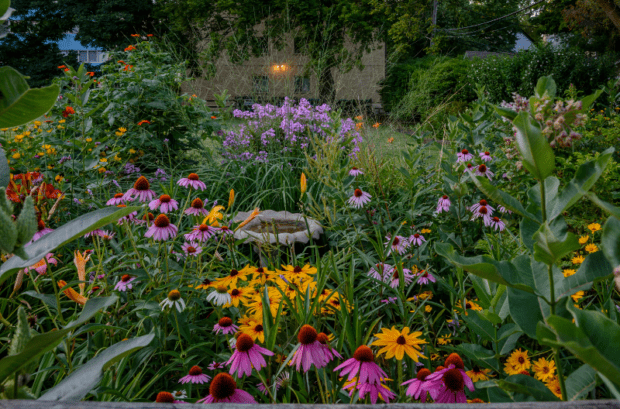

- Plant native blooming trees, shrubs, and wildflowers to provide pollinators with nectar and pollen to eat. There are plenty of helpful resources on native plants for your area. One of the most comprehensive ones is the Lady Bird Johnson Wildlflower database. If you live in the eastern portion of the country, you can order a pollinator plant pack directly from our Gardening for Wildlife store.

- Be careful about what plants you buy. Even though evidence is building that neonics are bad for bees, many commercial plants are still sprayed with this systemic herbicide before they are shipped to the big box stores and garden centers. Check the label of each plant for a warning to see if it was sprayed for aphids and other insects. If it is, then set it back down for pollinators’ sake.

- Plant for variety in color, sizes and seasons. Having a buffet of flowering options is best to help pollinators, especially bees. While many bees are generalists and don’t care about the flower species, there are some that are specialists (i.e. they only visit specific native nectar plant species). Some can prefer a certain size of flower so providing many different types of flowers is helpful. The What’s Buzzing in Texas? series will elaborate on this subject during a fall webinar, so keep an eye out for that date on the NWF’s South Central Facebook page.

- Provide nesting habitats for solitary bees. As mentioned above, solitary bees have different nesting needs than hive bees. Keeps areas of bare soil where ground-nesting bees can burrow. Provide pithy plant stalks like sunflowers where the bees can hollow out the inside for their nest. If you choose to use a bee hotel, they will need to be disinfected after every season to prevent the spread of bee diseases.

- Participate in citizen science activities! There are thousands of native bee species in the U.S., and there is still much we need to learn about individual species. Professor Beckhams credits observations from citizen scientists on iNaturalist to help track bees for her studies in Texas.

We also encourage you to learn more about how to conserve native bee species. Attend our What’s Buzzing in Texas? webinar series, or our Monarch Stewards workshops to learn more about how you can help conserve our native pollinators.