We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

The Evolution of Forest Resilience: Lessons from the Last 100 Years

Over the past century, our understanding of forest resilience has transformed from a model of control and suppression to one that embraces disturbance and diversity. This shift reflects a growing recognition that forests are not static resources to be tamed, but living systems shaped by complex, often unpredictable forces.

Today, forest resilience is not simply about returning to a previous condition after disturbance. Instead, it’s about building the capacity of ecosystems to adapt, reorganize, and even transform in the face of change. As climate pressures intensify, embracing this evolved definition is more urgent than ever.

According to the National Wildlife Federation’s 2021 report, Toward a Shared Understanding of Climate Resilient Landscapes:

“Resilience is not about preserving the past, but rather about maintaining ecological function and services in a rapidly changing world—and ensuring systems can adapt, reorganize, and even transform when needed.”

Let’s look at how we got here—and why science, humility, and partnership are more essential than ever for the forests of the future.

A Century of Change in Forest Management Thinking

In the early 1900s, forest management in the United States was driven by a philosophy of control. Wildfires were seen as destructive forces to be eliminated, pests as invaders to be eradicated, and forests as reservoirs of timber that needed to be cultivated and protected. This era was characterized by aggressive fire suppression, the promotion of monocultures, and replanting strategies that often ignored ecological complexity.

While well-intentioned, these practices had devastating unintended consequences: “Decades of fire suppression have led to unnatural fuel buildup, increasing the intensity and destructiveness of wildfires,” explains Bruce Stein, NWF’s Chief Scientist, in his report Climate Resilient Forests: Managing for Adaptation in a Changing World.

Without low-intensity, frequent fires to clear underbrush and recycle nutrients, forests became overstocked with fuel, making them more vulnerable to catastrophic wildfires, disease, and insect outbreaks. The very tools intended to protect forests often made them weaker in the long run.

The Rise of Ecological Resilience

By the 1970s, ecological research began to challenge the assumption that stability was natural or desirable. In 1973, ecologist C.S. Holling introduced the idea of ecological resilience, defining it as:

“The capacity of an ecosystem to absorb disturbance and reorganize while undergoing change so as to retain essentially the same function, structure, and feedbacks.”

This was a pivotal moment. Instead of trying to keep forests from changing, the new goal became helping forests change well.

Today, the science of resilience has matured, and with it, our strategies have evolved.

The 2021 NWF report highlights this progression clearly:

“Ecological resilience is not about avoiding change, but about ensuring that change does not result in the loss of core system identity or function. In some cases, resilience means enabling transformation.”

This nuance matters. Some forests may recover post-disturbance. Others may reorganize into something new—and that change may be necessary, even beneficial.

Building Resilience Through Adaptive Management

In today’s era of megafires, climate extremes, and species loss, adaptive capacity—the ability of ecosystems to evolve and reorganize in response to stress—is the new benchmark of resilience.

This is why adaptive management strategies now include:

- Prescribed fire to mimic the natural process of fire-adapted forests, while reducing the build-up of dried leaves, twigs, and trees that cause fires to burn hotter and faster.

- Selectively cutting some trees and saving others to replicate the heights, ages, and spacing of a healthy and resilient forest.

- Increasing the genetic and species diversity of trees to buffer against pests and climate shifts.

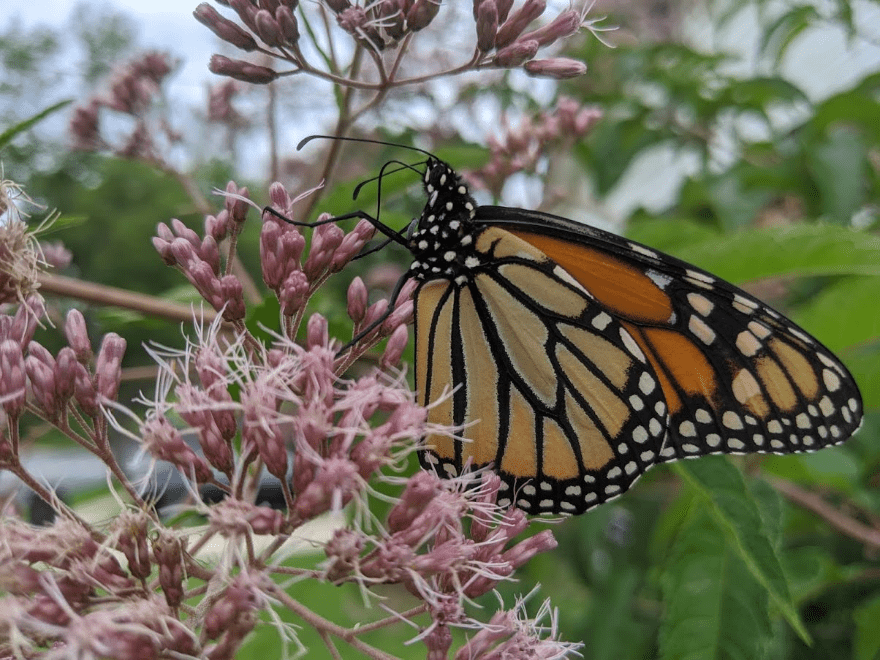

- Protecting and nurturing keystone species, such as white oaks and long-leaf pines, that provide an abundance of foods and living spaces for wildlife. Partnering with Indigenous land stewards to restore traditional ecological knowledge and practices that created the healthy and resilient forests that were previously found across North America

As detailed in NWF’s report, Toward a Shared Understanding of Climate Resilient Landscapes, true resilience is not just ecological. It is social, cultural, and political. Forest resilience depends on the systems we build around the land: inclusive partnerships, informed decision-making, and flexible policies that respond to on-the-ground realities.

Lessons for the Future

The biggest lesson from the past century is this: resisting natural processes weakens resilience; working with them strengthens it.

Instead of attempting to hold ecosystems in place, we must learn to steward their ability to change. We must invest in monitoring, research, and community engagement. We must center storytelling and data that illustrate how prescribed fire, diversity, and adaptive practices work in real time.

Forests are not problems to solve; they are systems to learn from. These approaches require collaboration, investment, and science-based planning and they also require new narratives about what success looks like.