We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Why are Bats, Owls, Toads, and Crows Associated with Halloween?

With the spookiest season in full swing and Halloween decorations abound, you might be wondering why certain animals are so often featured in our harvest-themed festivities. Why do plastic owls and crows decorate every lawn? Why does every depiction of a witch feature a toad? And why do fake bats seem to hang from every nook and cranny?

It turns out that the spooky mythologies surrounding these creatures are long-standing traditions that were developed from ancient humans’ understanding, or fear, of the natural world. This year, we are taking the opportunity to delve a little deeper into the strange stories of how these four groups of wildlife—bats, owls, toads, and crows and ravens—have become integral parts of our horror culture over the course of thousands of years.

Bats: A Tradition of Fear

Of all wildlife species, bats seem to be most intensively associated with Halloween; and for good reason— bats have been a symbol of the holiday since its origins. Given their tendency to gather in the autumn before migration and hibernation, swarms of bats are a common sight during dusk this time of year.

Halloween as we know it was thought to have stemmed from an ancient Celtic festival called Samhain (pronounced saw-wen), meaning ‘Summer’s End.’ During this time, the decaying of the land and oncoming darkness of winter was thought to evoke spirits from nearby ancient burial mounds.

To ward off those vengeful spirits, the Celts built huge, symbolically regenerative bonfires to invoke the help of the gods. These massive light sources attracted swarms of insects at night, which in turn attracted hunting bats. These opportunistic bats, swooping near the fire and capturing an insect before darting away, were interpreted to be the spirits of the dead which would only be scared off by their gods’ divine fire.

Christianity heavily influenced our views on bats during the Middle Ages. In the Bible, the bat is depicted as an inherently unclean animal unfit for consumption, perhaps because bat roosts can develop a layer of guano, or feces, on the floor which was rightfully associated with illness. But it was Dante’s Inferno, a 700-year old epic medieval poem, that solidified bats as an allegory for the devil and his domain. Dante’s still-famous poem described Devil’s wings as looking similar to those of a bat.

Associating with bats quickly became linked with witchcraft, an offense punishable by death. Even nobility could not avoid this association; a French noblewoman, Lady Jacaume of Bayonne, was burned to death simply because crowds of bats frequented her garden. In reality, those bats were likely taking advantage of the insects drawn to her flowers.

More recently, the author Bram Stoker added more fuel to the fire when he published Dracula in 1897. Dracula was described as a monstrous blood-sucking vampire that could transform himself into a bat. Stoker was inspired by real vampire bats, which feed on the blood of vertebrate animals—but they feed on wildlife and livestock, not on humans, and only drink a tiny amount of blood which leaves their hosts basically unharmed. And their victims don’t turn into vampires!

Owls: Soul Birds of Antiquity

Owls, like bats, are flying creatures of the night. But unlike bats, owls boast a more complicated mythos containing two conflicting depictions of the creature: one as a wise, helpful mystic and one as guardian of the dead.

This division seems to stem from the conflicting views of ancient Roman and Greek mythology. Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom, was often depicted with an owl companion. Athena’s owl was hailed as a symbol of knowledge and insight, and therefore owls were treated with reverence within Greek culture.

On the other hand, in Roman mythology the owl was a bird of ill omen that fed on human flesh and blood. When Rome defeated Athens in 146 BCE, this more malicious depiction of owls began to dominate both areas and spread into the world form there.

This depiction of owls was so pervasive that it affected Roman language. The Latin word ‘strix’ meant both ‘owl’ and ‘witch in the form of an owl.’ Romans did not always believe that owls were natural creatures, but instead were witches that had transformed into owls in order to fly to a Sabbath, a gathering of witches. Even today, ‘strix’ is used as the genus name for earless owls, including spotted owls and great gray owls.

The Roman concept of witches transforming into owls may have come from the myth of the harpy, a creature with the torso of a woman and legs and wings of a predatory bird. Interestingly, the harpy is thought to itself have been modified from the depiction of a soul in Egyptian mythology.

To Egyptians, Ba, or Ba-birds, were physical manifestations of the departed dead which had the body of a bird and head of a human.

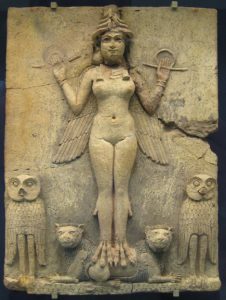

And it doesn’t stop there. A plaque from the Sumerian period, from about 1800 BCE, clearly portray a woman with feathered legs and owl feet, flanked by two owls.

This is thought to be a carving of Ereshkigal, goddess of the underworld, and the first ever depiction of a witch in association with owls, and origin of the Ba-bird. Remarkably, this means owls have been connected with witchcraft and the underworld for nearly 4,000 years!

Toads: A Witch’s Companion

Toads have long been associated with witchcraft, though their role in the demonic arts has shifted throughout history. The toad’s original association with witches probably came from the idea that toads are toxic, and could therefore be used to craft maleficent poisons.

Although biochemistry had not been invented yet, the poisonous nature of some European toads was well known by as early as 200 BCE. We now know that all toads in the bufo genus produce a sticky secretion exuded from their skin when threatened; a milky, moderately potent poison, called bufotoxin, that contains hallucinogens as well as other chemicals that can affect heart and motor function.

Though not a particularly potent poison, bufotoxin can be fatal in large doses, and it is likely that ancient peoples had become aware of this by watching other animals react poorly to eating toads.

With verifiably toxic capabilities, toads became a classic ingredient for any medieval mythological witch’s brew by the 1600s. Their association with witches was especially solidified in 1623, when Shakespeare published Macbeth and introduced Paddock, a witch’s toad familiar, in the opening scene of the play.

At this point, the toad’s role in witchcraft began to transform from a simple ingredient to a witch’s most trusted and intelligent demonic familiar. This shift in importance can be traced to the Spanish Inquisition of the 17th century. Specifically, in 1610 the Spanish inquisitors of Navarre reported that they had discovered a sect of witches in the nearby mountains. They claimed that the devil had been recruiting witches at an alarming speed in Navarre, and that he had gifted each new witch with a toad.

These were no ordinary toads, apparently, as the inquisitors described such a familiar as “…A demon in the form of a toad with its face like a man’s, dressed in finely tailored velvet and cloth.” This creature would become what was known as a ‘dressed toad,’ a hyper-intelligent maleficent force that called witches to Sabbath and instructed them in the Devil’s evil plans. According to the inquisitors, the witches fed human flesh to their dressed toads as reward for their assistance.

We may never know why the inquisitors of Navarre chose to embellish such a strange tale. In all likelihood, they sought to justify their war by claiming to rid it of what they considered a horrible demonic presence. At the end of the day, the moderate, defensive toxicity of bufo toads likely predisposed them to an association with evil intent—and the rest was history.

Crows and Ravens: Auguries of the Afterlife

Like owls, crows and ravens have a complicated, multi-faceted history in mythology. Across the world, these corvids have become known either as creative, intelligent mischief-makers, or messengers of the dead.

To many native tribes of North America, the raven was not only the creator, but also a fortune-teller, hunting companion, or informant. Some Sioux legends tell of chieftains who kept pet ravens that learned multiple languages and served as spies for their tribe. A similar legend exists in Norse mythology; Odin, the All-father, kept two ravens named Huginn (meaning ‘thought’) and Muninn (meaning ‘memory’) as informants on the world of men. Indeed, it is true that all corvids—including crows and ravens—can learn to mimic human speech.

In most cultures around the world, though, crows and ravens were not just seen as intelligent, but were also tightly linked to the realm of the dead. Edgar Allan Poe’s famous line “Quoth the Raven, ‘Nevermore,’” has had Americans associating ravens with demonic presences since 1845. In Germany, it was believed that ravens could locate the souls of the dead. In Sweden, the raven’s harsh calls were traditionally considered to be voices of inappropriately buried murdered people. Incredibly, paleolithic cave paintings found in Spain and France, made some 15,000 years ago, include images of ravens sitting on posts near burial sites— meaning it is possible that these early cave people already worshipped ravens as guides to the afterlife.

Even the Qur’an’s version of the story of Cain and Abel features a raven who taught Cain how to bury his murdered brother. In the story, Cain, having murdered Abel, did not know how to dispose of the body. Looking around he noticed two ravens—one dead, and one alive. The living raven dug a hole in the ground in which it buried its dead mate, revealing the solution to Cain.

This tale may have been based on observations of real crows. Although crows have never been known to bury their dead, they do use their beaks as a digging tool, and they have been observed to ritualize the death of their own kind. These ‘funeral’ rituals consist of several crows surrounding their dead companion in a big, raucous mob for about twenty minutes. It is thought that crows do this to investigate and share information about the circumstances of the death, so that they can all avoid a similar fate.

Why are corvids so often associated with the afterlife? These birds’ common practice of scavenging no doubt spurred associations with death, especially in autumn when inexperienced animals begin to die in large numbers as their summer resources dwindle.

In addition to scavenging the bodies of other wildlife, crows have also long been associated with battlefield graveyards, where they are often seen taking advantage of an abundant food resource. Because they couldn’t break human skin very well, these crows tended to eat the eyeballs or other soft tissue first— an understandably gruesome sight.

Corpse eating became an especially potent problem for the crow’s image during the Middle Ages, when the Black Death, an outbreak of the plague, devastated Europe and killed around 50 million people. With an excess of bodies filling the city streets of Europe, the crow’s opportunistic eating habits were suddenly visible to many scared and confused people.

During this time, plague doctors began wearing costumes with masks similar in structure to a crow’s face. At the time doctors did not know about germs. They assumed the plague was transmitted by ‘bad air,’ and put fragrant herbs in the mask as an attempt to keep them from falling ill while treating patients. The shape of the beak was supposedly designed to give the air enough time to be cleansed by the herbs before it reached the doctor’s nose.

In reality, the disease was caused by bacteria and was transmitted through flea bites or contact with the infected. It was the plague doctor’s protective suit, gloves, and prodding cane that kept them at lower risk of infection, not the crow-shaped mask. In any case, the plague doctor’s crow mask, seen when they were handling patients that would almost certainly die, undoubtedly fueled anti-crow sentiment across Europe.

The truth is that the crow’s tendency to scavenge on anything available—including human corpses—has been beneficial to both humans and other wildlife. Crows and other corvids serve as nature’s clean-up crew by removing carcasses from the environment that would otherwise become bacterial and viral breeding grounds!

Halloween is a time for family fun and spooky decoration. But as we ramp up for the scary season this year, take some time to appreciate the fascinating and complex creatures that we love to fear. These “scary” creatures pose no real threat to humans; in fact, many of these animals should be scared of us. The National Wildlife Federation is working every day to protect our most endangered species for many Halloweens to come. Here is how to support and contribute to NWF.