We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Troubled Waters – Mysterious Wildlife Deaths in Indian River Lagoon

At Indian River Lagoon, this nightmarish scene is real.

An Engineered Landscape

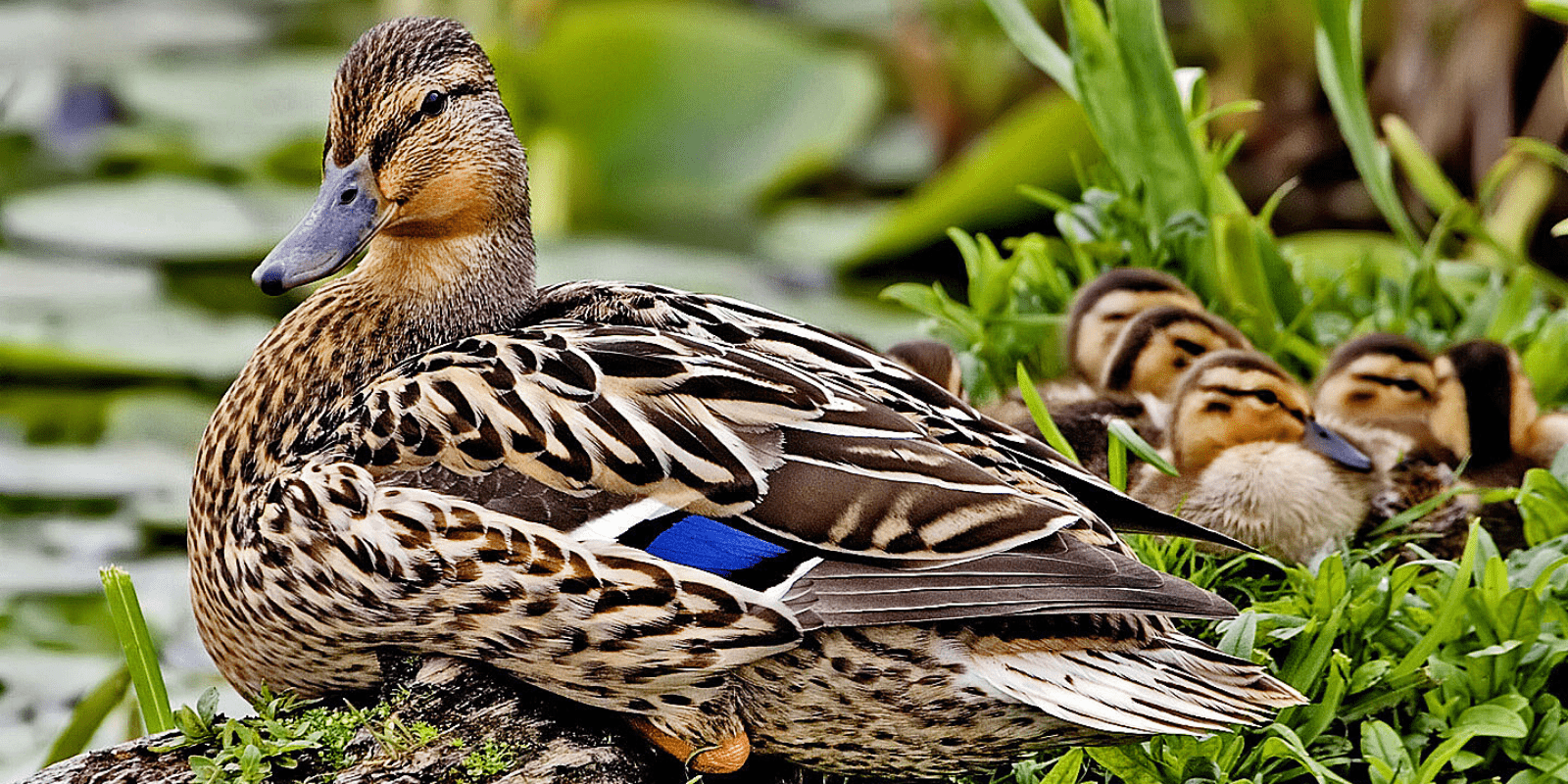

Indian River Lagoon stretches along 40 percent of Florida’s east coast, 156 miles long and encompassing Mosquito Lagoon, Banana River, and Indian River. Its estuarine waters are brackish, a mix of fresh and salt water and support roughly 685 fish species, 370 bird species, and 2,200 animal species.

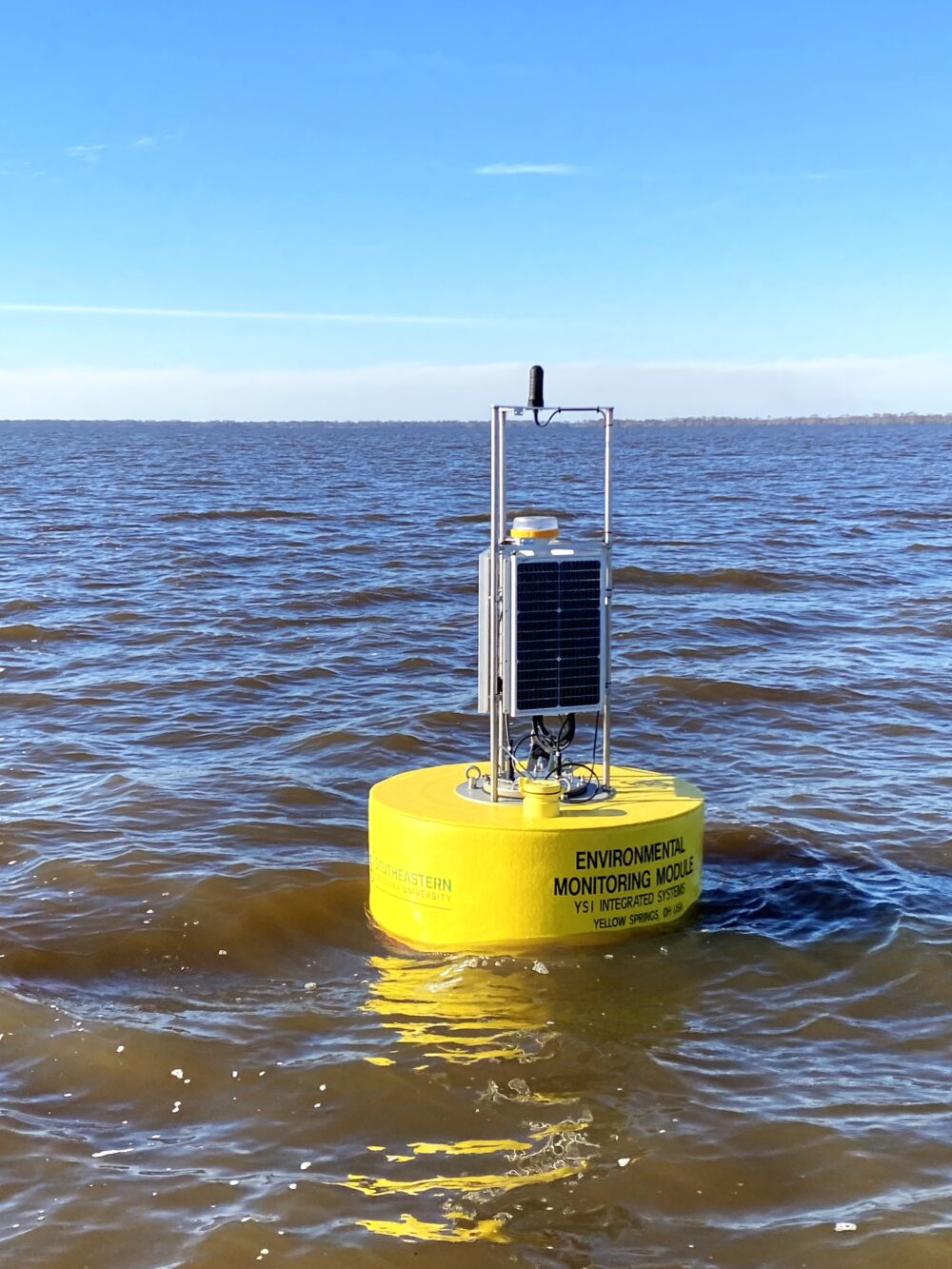

Like most of Florida’s water ecosystems, Indian River Lagoon has felt the impacts of Florida’s zealous history of development, diversions, and engineering manipulation. As part of the nation’s crusade to control water in South Florida, Congress authorized the Army Corps of Engineers to construct a dike around Lake Okeechobee in 1948. Now, the Corps is required to carefully monitor the lake’s levels and periodically release discharges of nutrient-rich freshwater from Okeechobee to the west (Caloosahatchee River) and east (St. Lucie River), where it eventually enters Indian River Lagoon.

A Death Trap

To complicate the issues plaguing the lagoon, an enigmatic slew of dolphin, manatee, and pelican deaths have erupted in the last year. Fifty-one dolphins, 111 manatees, and over 300 pelicans have died in the lagoon since last July.

What is even more perplexing is that the pelican and dolphin carcasses found are emaciated, while the manatee carcasses appear outwardly healthy, with traces of the typically non-toxic macroalgae Gracilaria lining their digestive system. A federal researcher with National Ocean Service has recently found three varieties of toxins from microscopic algae that cling to the Gracilaria seaweed, which may be the cause. However, it’s still unclear what algae or group of algae is producing the toxins and how to counteract it.

One thing , however, is certain: manatees and fish have been consuming more of this red drift seaweed — and presumably the toxins that stick to it — since their main source of food, seagrass, has been killed by previous algal blooms in the lagoon.

The St. Johns River Water Management District has committed up to $3.7 million to research the previous algal blooms and help protect the estuary in future.

There are only about 5,000 manatees in Florida.

Let’s Protect Paradise

Since Governor Rick Scott was elected in 2009, Florida’s regulation, conservation, and water programs have suffered severe cutbacks, essentially reversing much of the progress Florida has made towards improving land and water conservation since the 1960s.

If the Indian River Lagoon death trap is any indication, these cuts and poor water management practices have done nothing but dilute the protections meant to guard Florida’s water resources for Floridians and for our wildlife.