We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

More Corn Ethanol, Less Water for Wildlife

New Research Details Threat to Western Water from Corn Ethanol

It may be hard to imagine water scarcity, given that large swaths of the Midwest are still drying out after historic and catastrophic flooding, but recently released research points to a different menace in the cycles of Western Water woes: corn ethanol.

Researchers from the University of Wisconsin-Madison teamed up with colleagues from Kansas State University and the University of California-Davis to analyze how the federal program that requires the use of corn ethanol and other biofuels in our gasoline is impacting the environment. They came up with some groundbreaking – and concerning – results.

Ethanol Production Drives Water Use

Considering some of these findings begins to paint a picture of just how much water ethanol production has been sucking up:

- In 2012 – in the midst of a devastating drought – some ethanol refineries in arid states (Arizona, Idaho, Wyoming) were producing ethanol from corn that had required more than 2,000 gallons of irrigated water for each gallon of ethanol produced. Several others (in California, Nebraska, and Oregon) required more than 1,000 gallons of water per gallon of ethanol if made from locally irrigated corn.

- Additional cropland, incentivized by the federal ethanol mandate, used 16.7 billion gallons per year of more water (from any source) than the grasslands and natural vegetation that would have been there without the biofuel demand.

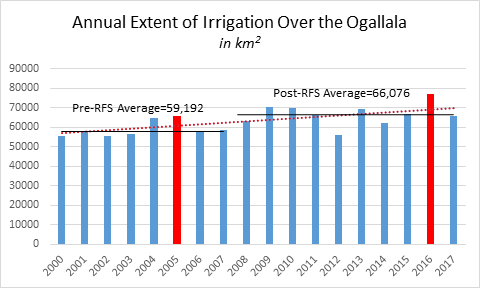

- Irrigated farmland over the Ogallala Aquifer – a critical water resource that feeds one-fifth of the agricultural production in the Great Plains – increased from 2000 to 2017, and the increase sped up following creation of the mandate in 2007.

Ethanol’s Connection to Water Scarcity

It has been more than 10 years since the Renewable Fuel Standard was created, and in that time there have been mounting reports on a variety of aspects linked to the growing demand for corn and soybeans to produce fuel, culminating in last summer’s massive report from the Environmental Protection Agency to Congress outlining the negative environmental impacts of biofuel production. The report focused on how the additional crop demand led farmers to plant a lot of new acres – primarily of corn – and how that meant less wildlife habitat and water filtration, and more application and erosion of chemical fertilizers that end up polluting our waterways.

The new research adds necessary context and depth to that body of knowledge, but they also point to a new problem: thirsty new corn acres in arid regions of the country are adding to the already highly strained water resources in many places.

Take, for instance, ethanol plants in places like Arizona and Idaho. You would not normally think of Arizona as a corn growing state. But for an ethanol production plant to be economical, it typically has to source its corn from within about a 50-mile radius. Otherwise, the cost of transporting the corn long distances outweighs the benefit of converting it to fuel and selling it.

What you get as a result is something like Pinal Energy, a small ethanol refinery just south of Phoenix. Even though it is situated right next to the Sonoran Desert National Monument, the plant is surrounded by crop fields that require lots of water to grow. In fact, an analysis by the University of Wisconsin found that the plant was surrounded by some of the most water-intensive ethanol feedstock in the country, requiring 2,667 gallons of irrigation on the surrounding corn fields to produce just one gallon of ethanol. In contrast, it typically requires between one and 2.5 gallons of water to refine a gallon of gasoline. If the irrigation rate in 2012 were constant and the plant sourced all its corn from nearby fields, this one facility would require more than 133 billion gallons of irrigation every year to meet its operating capacity of 50 million gallons of ethanol.

The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that in 2015, Maricopa County where the plant is located consumed 1.2 billion gallons of water for irrigation every single day, which would mean 438 billion gallons a year. Therefore, at 2012 irrigation rates, Pinal Energy could be sucking up one-third of all of the irrigation in the county, helping make it the largest irrigated county in the state, and one of the largest in the entire country.

Compare this to the USGS estimate that one adult typically uses 80-100 gallons of water a day. Using the high, end of that range, corn for the Pinal facility guzzles as much water as 3.6 million people! That’s about the size of the population in Oregon or Oklahoma.

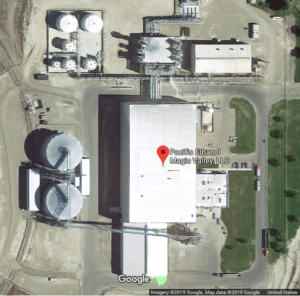

Heading north, southeast Idaho is one of the most heavily irrigated regions of the country, growing an array of crops including the famous potato. The county drawing the second-largest amount of water for irrigation in the state is home to the Magic Valley plant owned by Pacific Ethanol. It ranks second in the University of Wisconsin’s irrigation intensity ranking for current plants (the No. 1 facility in Wyoming has gone out of business), requiring 2,022 gallons of irrigation on the surrounding corn fields for each gallon of ethanol they could be used to produce. At its capacity for 60 million gallons of ethanol per year, its use of 121 billion gallons of irrigation water each year account for 34 percent of that county’s irrigation consumption at 2012 rates. That’s the amount of water that every person in Idaho and neighboring Montana and Wyoming use in a year.

Facilities in California and Oregon also had very high irrigation requirements on the surrounding fields, surpassing 1,300 gallons of irrigation per gallon of ethanol. Refineries in Nebraska and Texas, while not quite the water guzzlers as their peers, do sit over the Ogallala Aquifer which is critical to America’s grain, cotton, and beef production and is being tapped at highly unsustainable rates.

Another UW analysis looking at the Ogallala Aquifer, specifically, showed that conversion of land into irrigated agriculture accelerated once the ethanol mandate spurred a jump in ethanol production. An increase in water use followed. The average amount of irrigated fields in the seven years following creation of the RFS was 9.75 percent higher than the average in the 7 years prior to the program. The year with the most irrigated land in the 7 post-RFS years saw 7.1 percent more irrigated land than the highest year pre-RFS.

Water – and Wildlife – in a Changing World

Clearly, ethanol production is not solely to blame for the West’s struggles with water availability. But, this new data paints a clear picture of how ethanol facilities can have outsized local impacts in areas that are already dealing with water scarcity, making it even harder for farmers, their communities, and the wildlife that also depend on scarce water resources to cope with shortages and adapt to the variations brought on by climate change.

As we’ve reported, our western water is already stretched thin and under increasing demands due to a warming climate and its impacts on mountain snows, spring runoff, and late-season water availability for native fish. Innovative water conservation campaigns range from incentives for lawn removal to water leases to convert agricultural irrigation water to instream flows for fish and recreation.

As described by National Wildlife Federation’s Sarah Bates, some cities require conservation offsets for new construction for “water-neutral” growth. In other words, westerners are stretching their limited water as far as possible.

In light of these initiatives and the growing concern over water in a warming West, it defies logic to have a federal mandate that drives up water consumption.

Today’s flooding will soon give way to tomorrow’s dry conditions, meaning wells all across the West will start pumping to feed corn headed to ethanol plants. It is time for policy makers to ask if that is the best use of those water resources.

The National Wildlife Federation has continually pressed the EPA to change its implementation of the biofuel mandate, and earlier this year sued the agency for failing to follow the law to protect wildlife. We were also supportive of bills introduced in the House and Senate last year that would shift the emphasis of the law away from fuels made from resource-intensive corn and soy, and instead favor more sustainable alternatives.

Take action: Call on Congress to stop to the destruction of our scarce, remaining grasslands:

Take Action!