We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Harvey: With Climate Change, Unprecedented is the New Normal for Wildlife

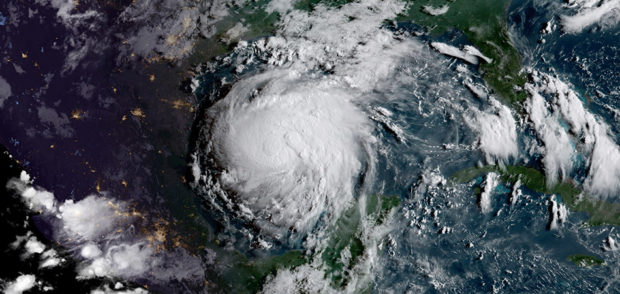

The word unprecedented is being thrown around a lot these days. After Hurricane Harvey battered Texas with record rains and as Hurricane Irma bears down on Florida and the Caribbean, we give our thoughts to those whose lives and property are in harm’s way and hope for their safety as rescue efforts continue. The impacts to people and wildlife will be immense, and our immediate thoughts should be to helping those in need.

Yet, it is critical that we discuss the new reality we face. It is past time that we can confuse the “unprecedented” nature of this hurricane with meaning it is anomalous or freakish. Quite unfortunately, storms like Harvey and Irma are going to be all too normal because we have a dangerous, new climate to contend with.

Climate change is no longer an abstract future occurrence. We are now in the era of climate change. Harvey is supposedly a millennial flood – meaning a once in a 1,000 year flood. Yet, it is the third 500 year flood to hit the Houston area in the past three years. That means that Houston has had for three years in a row a storm with a .2% chance of happening in any given year based on the way the climate used to be. Since the 1950s, Houston has seen a 167% increase in the frequency of its most intense downpours. Harvey is likely to be the most expensive natural disaster in U.S. history, surpassing other unprecedented, but recent, events such as Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy. Irma has winds measured at an ungodly 185 miles per hour as it charges through the Caribbean.

Hurricanes and Climate Change

The relationship between hurricanes and climate change is a bit like the steroid era in baseball. Rampant steroid use by professional baseball players in the 1990s did not necessarily cause more hits to occur, but changed the nature of those hits. Suddenly, rather than singles, doubles or triples, batters started hitting a freakish number of home runs. Likewise, while hurricanes have always been a reality in the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico, climate change is increasing the severity and intensity of those that occur and making them much more destructive and dangerous.

In short, as climate scientists have pointed out, there are at least a few ways that climate change has almost certainly worsened the flooding.

-

Sea level rise. More than a half a foot of sea level rise can be attributed to climate change. This means that for coastal areas, the storm surge for Harvey was at least half a foot higher as a result of climate change. As a result, a higher surge reached further inland. Additionally, water falling on the mainland is backed up by this increased surge and unable to drain seaward, also adding to flood levels.

-

Rainfall intensity. Sea surface temperatures have risen about a 1 degree Fahrenheit over the past few decades, and this year saw temperatures about 4 degrees F above normal, according to a research meteorologist with National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Hotter ocean temperatures mean more moisture in the atmosphere, which means more rain. Climate models show rainfall rates in hurricanes in warmer climates increasing about 20% near the center of hurricanes.

-

Overall storm intensity. Climate change also likely added to the intensity of the storm itself. With warmer oceans creating energy for the storm, Harvey intensified as it approached land, which is unusual. But climate change may make this occurrence more common, meaning more destructive and faster brewing storms.

There are also studies showing that changes in the jet streams and high and low pressure systems that have allowed the storm to effectively stall, increasing the duration during which it is allowed to dump moisture on the Houston area.

The Houston area has additionally experienced immense sprawling growth. The increased amount of impervious surface that doesn’t absorb water and the Houston area’s naturally poor draining soil also increased the intensity of the flooding.

Contending with Climate Change

Again, caring for the people impacted by this disaster as well as the victims of Irma is the highest priority. But it would be irresponsible to ignore the new world we are in and not take swift actions to keep it a safe place for people and wildlife.

There is a two pronged approach to confronting climate change. The first is referred to as “mitigation.” This means addressing the cause of climate change – emissions of greenhouse gases that trap heat and alter the climate. We must quickly convert from fossil fuels to clean energy sources, as well as change land practices primarily in forestry and agriculture to ensure that these practices store carbon in plants and soil, rather than releasing them into the atmosphere.

The second is referred to as adaptation. This means making infrastructure and natural resource management decisions that plan for and reduce the impacts from the new climate reality. We need to rethink how we manage our cities and ecosystems, and protect, enhance and restore natural features such as wetlands, to better protect people and wildlife from the events such as major rainstorms and hurricanes.

Clean Energy is More Resilient

Harvey is also illustrating how clean energy can make communities more resilient to major, climate exacerbated events. Under a fossil fuel-based energy system, energy production is centralized. Much of our oil refining capacity is concentrated in the Houston area. Harvey is temporarily shutting a great deal of this refining down. This leaves our transportation sector vulnerable to interruptions in fuel distribution and potential gas spikes. For the people and wildlife of Houston, it creates severe pollution problems, as the refineries become huge sources of toxic contamination when pollution contained at these plants mix with flooding waters and escape into the environment.

A clean, more distributed energy system based on sources like wind and solar not only eliminate carbon pollution, but it is more resilient and less polluting. A system with more distribution and diversity does not pose the vulnerabilities of a more centralized system where a large portion of refining or distribution capacity can be knocked out by extreme events. For instance, owners of electric cars are not disturbed by interruptions in centralized gasoline refining and resulting supply shortages and price spikes. And solar panels and wind mills do not become sources of severe pollution when flooding and other events occur.

The Path Ahead

We must move aggressively ahead on both mitigation and adaptation policies to protect people and wildlife because climate change in upon us. There is reason for hope as renewable energy development is increasing and many states, businesses and localities move swiftly to act.

Sadly, our current Administration is in full throttle reverse, pulling out of the landmark Paris Agreement where virtually all countries committed to keeping climate change at safe levels and dismantling a host of policies and scientific endeavors designed to protect wildlife from climate change and inform the public about coming changes. It is important that states, cities and private actors pick up the slack, but we need federal action to achieve the type of pollution reductions needed.

We now live in a more dangerous world. With a commitment to making the right type of changes, we can maintain a stable, safe and clean future for wildlife and people. But as Harvey and Irma are showing us, the cost of inaction is unthinkable.