We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

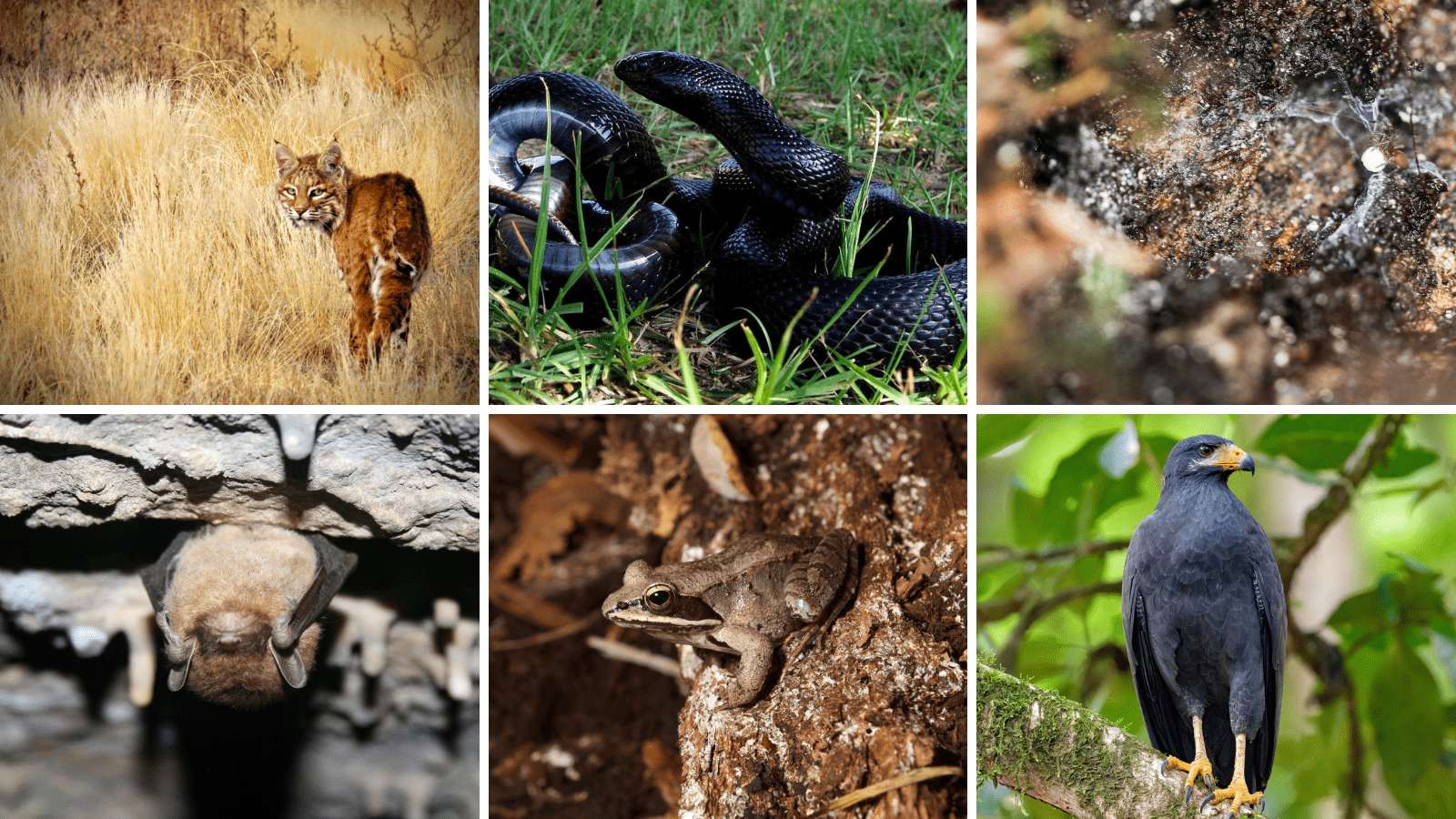

6 Spooky Species (That Need Our Help)

Extinction is the real terror this Halloween – fully a third of American wildlife species are at some level of increased risk. Critters with sharp teeth, slithery scales, and hairy legs may seem like they can fend for themselves. But the reality is that threats like climate change and habitat loss are hurting them, too.

Here are six species traditionally considered spooky or scary – that actually need a little help from us.

The spruce-fir moss spider: tiny & mighty but endangered

Our diverse and unique public lands in the United States are home to special habitats and ecosystems that may not exist anywhere else in the world – which means that they’re also home to species that don’t exist elsewhere.

The spruce-fir moss spider, the world’s smallest tarantula, only lives in the highest elevations of the Southern Appalachian Mountains. Its world matches its size: This tiny spider thrives in a microclimate of moss mats on boulders kept damp by Fraser fir trees above the boulders.

While the spruce-fir moss spider makes spooky cobwebs for itself to attract prey, that doesn’t mean the species as a whole is thriving. An invasive insect has been killing the Fraser fir trees responsible for keeping the spider’s mossy home damp. The double threats of climate change and habitat loss through logging are hurting this arachnid, too, which is why it’s been listed as endangered since 1995.

Little brown bats are facing a frightening problem

Infested with disease and blood-sucking with a penchant for human victims? It’s pretty batty that bats are the only mammals that can fly, but U.S. bat species aren’t anything like Count Dracula. While bats do host a number of viruses that can be transmitted from animals to humans, they don’t roam the skies looking for people to infect with disease – if anything, they want to keep their distance from us, but sometimes habitat loss gets in the way of that. Giving bats lots of space and staying out of their habitat reduces disease transmission, and human cases of rabies are very, very rare.

In fact, bats help humans out big-time – little brown bat colonies can consume thousands of pounds of insects each year, including crop pests that cause problems for farmers.

The scary truth about little brown bats is that their U.S. populations have declined by 90% over the course of a decade due to white-nose syndrome, a fungus that grows on their skin and causes hibernation problems, dehydration, starvation, and death. As one of the most common bat species in the U.S., it’s concerning that even little brown bats need proactive conservation actions thanks to how much white-nose syndrome has decimated their colonies.

Like most wildlife species, little brown bats can benefit when people build havens like bat houses in their yards for them – and if you want to help them, taking other steps to Garden for Wildlife is effective, too.

No “purranormal cativity” here – just bobcats!

The most common wildcat in the U.S., bobcats tend to make themselves scarce – it’s quite rare for a human to spot them. However, that doesn’t mean they’re assisting witches with occult activities in the dead of night. Instead, they prefer to hunt at night. Like many other predators at the top of food webs, bobcats act as a keystone species in their ecosystems – they keep other populations of wildlife in check and prey on sick or weakened individuals.

While bobcats are not federally listed as threatened or endangered, they’re still dealing with the threats that all wildlife face these days: climate change, habitat loss, pollution, and more. The beauty of the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act, which has been introduced in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives by a bipartisan group of senators and representatives, is that it allocates resources to states to take proactive action to conserve wildlife before they need the emergency-room protections of the Endangered Species Act.

State fish and wildlife agencies are experts on the challenges facing wildlife in their states. For example, in New Jersey, The Nature Conservancy partnered with the Division of Fish & Wildlife to restore habitat for bobcats, which nearly went extinct in the state. We think that’s pretty meow-some!

Witching hour or water shortages? Both are chilling!

Spending part of its year in the Southwestern U.S., the common black hawk cuts a formidable figure and feeds on other spooky critters, including frogs and lizards.

Thanks to climate change, the West has been increasingly dealing with droughts and water shortages. This problem is hurting wildlife and humans alike – the common black hawk, for example, only lives and hunts near flowing streams in the U.S. portion of its range. It also spends its time near streams courting and raising young, so the presence of water is vital to its life cycle.

Smart water management is important to adapting to climate change for both Western communities and wildlife. Read more about the National Wildlife Federation’s work to conserve Western watersheds and rivers here.

What’s the fun in being a big, scary snake if your habitat is disappearing?

While the handsome black pinesnake might seem like it would be at home in a dungeon or creepy crypt, it actually lives in the sunny longleaf pine forests of the Southeastern U.S.

Once one of the most sprawling ecosystems in the U.S., longleaf pine forests only exist in 3-4% of their historical range today due to development, habitat fragmentation, and fire suppression. Fire plays a critical role in the longleaf pine ecosystem – it keeps the forest floor free of hardwood tree species, allowing wildlife species to build nests and dig burrows in the sandy soil. Black pinesnakes spend much of their time in burrows and even hunt small mammals by trapping them in tunnels and squeezing their bodies against the tunnel wall, trapping and suffocating their prey. Clearly, the longleaf pine forest is critical for the long-term survival of the black pine snake. Since 2007, the National Wildlife Federation and Alabama Wildlife Federation have collaborated with private landowners to restore this incredible habitat so that these snakes can do what they do best – scaring the smaller members of their food chain. Read more about this restoration work here.

“Zombie” frogs are hurt by pollution, too

Wood frogs, which primarily call Alaska and the Northeast home in the U.S., are practically members of the living dead – during winter, they literally freeze and later reanimate. How do they pull this off? Well, they stop breathing and their hearts stop beating, but they produce a special glycerol-based substance that acts as antifreeze and prevents ice from forming within their cells. If the water within a cell were to freeze, it would expand and the ice crystals would tear the cell apart, killing the frog. Through this process, nearly 70 percent of the frog’s total body water is converted to ice. This adaptation allows the wood frog to survive even in the Arctic.

Despite this preternatural trick, life isn’t all treats for wood frogs and other amphibians. In fact, amphibians are the most threatened class of vertebrates on the planet. With semipermeable skin and porous eggs laid in vernal, or seasonal, pools of water, wood frogs are at a higher risk of being affected by pollution, climate change, and disease. In other words, we’ve got to keep our land, air, and water clean so this friendly zombie can keep freezing itself to its heart’s content!

If you also agree that the threats facing these species are goosebump-raising, then we’ve got the perfect action for you to take. The Recovering America’s Wildlife Act was drafted to help all of these species and so many more by investing in conservation work done in every state and by federally recognized tribal nations. This legislation needs as many congressional champions as possible. Tell your representative and senator to cosponsor Recovering America’s Wildlife Act today so that all of these amazing, spooky species can get back to what they do best – sending shivers up our spines!

LEARN ABOUT RECOVERY .