We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Making Moves: Canada Lynx in Vermont

This year has brought exciting insight into the distribution of Canada lynx in the Green Mountain State.

Having predominantly only been observed in the northeastern-most portion of the state, biologists now have two compelling pieces of evidence to suggest this federally listed species is roaming the wilderness of southern Vermont.

This June, a solitary Canada lynx was photographed outside a rural home in Londonderry, Vermont, marking the first confirmed evidence of lynx in Vermont outside the Northeast Kingdom in decades. Just recently, a second photograph emerged that biologists suspect is also a lynx in the nearby town of Searsbury, Vermont.

The second photo was discovered by a University of Vermont Student who was using wildlife cameras to document bear movement across Route 9 in Searsbury, VT. While reviewing photos collected during the project, the student found a photo showing a “wildcat” passing under Route 9. The photograph was taken at a wildlife underpass created in partnership with the Staying Connected Initiative by the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department and VTrans.

“This is very exciting news for Vermont,” said Chris Bernier, a furbear biologist for the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department. “The fact that this animal chose to travel such a long distance demonstrates why it is vitally important to maintain healthy and well-connected habitat in Vermont. We were thrilled to see the animal using a wildlife underpass that was created for the express purpose of allowing animals to pass safely under the road.”

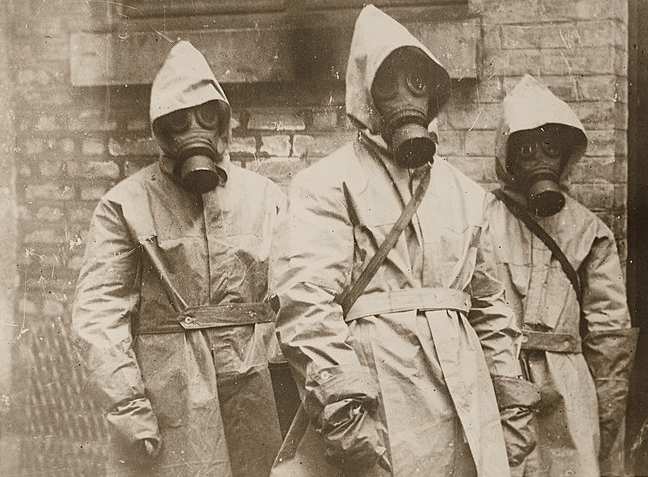

Shadows of the Northern Forest

Historically, lynx sightings have been notoriously rare – so rare that they were thought to be nearly extirpated. From the late 1700s up until 2003, there were only four confirmed sightings of lynx in Vermont. Since 2003, that number has continued to rise along with optimistic notions of this species’ ability to persist in the Green Mountain State. For example, in 2012 biologists discovered evidence of a family of four lynx traveling together in the Nullhegan Basin in the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont. This is the first time in Vermont’s history that a reproductive lynx has been documented.

Yet, “Vermont has never had a large or stable lynx population,” said Bernier. Lynx primarily occur in large, unfragmented, mixed-conifer forests and as a specialist species, their distribution is strongly linked to snow depth and snowshoe hare, their primary food source. Their thick coats, long legs, and large saucer-like paws have uniquely evolved to provide them with a competitive advantage in deep snow habitats. But, as climate change threatens to significantly reduce the snow cover on which this species depends, the lynx will lose this competitive advantage. A warming climate will favor more adaptable predators, like the bobcat and fisher, who prey on a more diverse range of animals.

Keeping up with Climate Change

Warming temperatures and reduced snow cover will likely force Canada lynx to move north in search of new, suitable habitat. For populations occurring in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine, the options are limited.

The St. Lawrence River, which separates these northeastern states from the majority of Canada, represents a significant barrier for land-bound mammals because it is kept free of ice in the winter for ship-borne commerce. Northeastern populations of lynx may become trapped and will be eventually restricted south of the river to the high elevations of the Gaspe Peninsula of Quebec (the northernmost limits of the Northern Appalachian-Acadian region). Maintaining appropriate habitat and space for lynx to move is vital to ensuring this species persistence in this region.

Securing a Future for Lynx

To combat the impacts of habitat fragmentation and climate change for imperiled species like the lynx, the National Wildlife Federation’s Northeast Regional Center has teamed up with two dozen public and private entities to maintain, enhance, and restore landscape connectivity for wildlife across the Northern Appalachian-Acadian region.

Collectively known as the Staying Connected Initiative, NWF and its partners are working to conserve key linkage areas that are critical for lynx, bobcat, bear, moose, and other far-ranging mammals to migrate as their habitats change in response to climate change. By maintaining existing links in the landscape and preventing further habitat fragmentation within the linkage areas, NWF is working to ensure that wildlife within our region have the ability to move where, when and as far as needed.

Help LynxHelp the National Wildlife Federation work to conserve critically imperiled wildlife like the lynx!