We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Measuring Conservation & Community Stewardship

Perspectives on Community-Academic Partnerships to Create Engaged Environmental Research

NWF EcoLeader Community Research Fellowship

As a doctoral student in urban planning and public policy with a focus on environmental policy and community stewardship, finding ways to strengthen community-academic partnerships has been important in my academic work.

When I wrote out the proposal for the NWF EcoLeader Community Research fellowship, I was keen to chart out how academic institutions associated with NWF were developing successful long-term community relationships. NWF has strong relationships with academic institutions through their programs like Ecoleaders, Campus Race to Zero Waste, and others. They also have strong relationships with community groups and organizations that are supporting grassroots environmental movements.

NWF’s existing community and academic relationships across the nation were an opportunity for me to reflect on the question, who is doing engaged environmental research? and how do they keep doing those things through time?

The NWF EcoLeader Community Research Fellowship provides an opportunity for graduate students like me to support the growth of NWF’s community-based programs by researching minority-serving academic institutions that are doing community-based environmental work. This type of fellowship work helps to analyze and present models and practices that academic institutions use to create long-term meaningful relationships, enact lasting change, and help to build the environmental stewardship capacity of historically marginalized communities.

Researching conservation practices

Academic research in environmental conservation shows that underserved and minority communities suffer disproportionately from environmental hazards. There is a growing need to develop innovative methods of researching environmental conservation practices that result in a community knowledge base ingrained in everyday community stewardship.

Partnerships between community residents and academicians can improve the environmental health of communities and the knowledge required to maintain them. When academic institutions and community members are engaged in environmental research, they have proven effective in sustaining long-term university-community partnerships, generating high-quality data, and gathering shared knowledge.

While it is normal for academic environmental research to address equity and justice in their process of engaging with communities, there continue to be academic projects that largely focus on addressing environmental issues without tackling their relationship to environmental justice. I was keen to address this gap with the fellowship research with NWF. As a fellow at NWF, I got the opportunity to reach out to NWF’s network of minority-serving academic institutions from across the nation, that have faculty, staff, or students who have successfully completed engaged environmental research.

Community influence and outcomes

After shortlisting a list of faculty and staff, I interviewed the academic partners and the community partners, that had partnered in successful engaged environmental research. In these interviews, I had the opportunity to discuss the ways in which engaged environmental research has been implemented to date in the broader environmental research field. The research projects were from different departments ranging from architecture and planning, Environmental Science, Sustainable Development Institute, Native Environmental Science, and Applied Environmental Health Department.

We also discussed the ways in which community involvement in the research process influenced the outcome of the project, in comparison to the intended outcome that was set up at the start of the project. Lastly, we touched on the criteria and scope of the grants that allowed community partnership to be a driving force of the research project, as well as the location’s geographic, historic, and cultural significance as the place to address environmental justice in the broader regional context.

Analysis

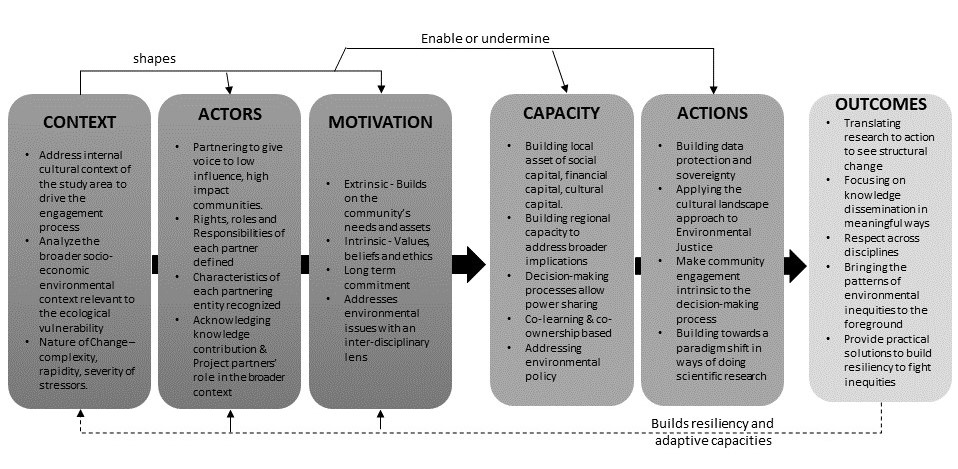

The framework in figure 1 captures the elements of partnerships that support locally created stewardships and have been pivotal in making environmental concerns part of people’s everyday practices. I found that when such stewardships emerged or were strengthened with a partnership, they provide mutual benefits and long-lasting relationships between the community and the academic institutions and helped to mobilize collective action, beyond the project scope.

With this research, I heard many stories about long-term relationships between the community and academic partners. Participants mentioned the need for a thorough understanding of the internal socio-economic, environmental, and governing context of the place to successfully build community stewardship.

For example, for the College of Menominee Nation, the cultural identity of the academic institution parallels the cultural identity of the tribal community. “When the college came into being the Trib[al] community was the force behind the creation of the Sustainable Development Institute” (Academic Partner). This had ensured a more internalized process of engagement between the college and the community so that one could not operate without the other’s input.

In some other partnerships, there was an external Environmental Justice (EJ) framework put in place within the academic institutions to ensure impactful community. So, either the academic lab that the researcher was associated with had an EJ framework in place for all research projects associated with the lab, or partnering researchers’ education, background, and ethical principles ensured that the project had an impactful engagement process.

I observed that the partnering communities in all cases were socially vulnerable, due to the broader regional socio-economic context standing in contrast with the community’s social identity. The CDC defines social vulnerability as “the potential negative effects on communities caused by external stresses on human health. Such stresses include natural or human-caused disasters or disease outbreaks.”

While partnering with socially vulnerable communities, the academic partners ensured that they addressed the environmental challenges with an interdisciplinary lens. For this to happen, the project scope of all cases “acknowledged working through the political and ethical challenges posed at the project sites” (community partner) which were in many cases more important than the technical environmental characteristics of the site.

This meant recognizing the patterns of urban pressures that ecologically vulnerable communities were faced not just within the study area but also recognizing how those patterns were repeating in other similar contexts elsewhere in the region will help to build a network of capacity. When multiple high-impact but low influence communities of a region form a coalition that supports each other and brings about positive ecological changes in the region, they build a network of capacity.

The interviewed academic and community researchers noted that there is a legacy of structural and systemic inequality in the ways in which decisions are made for the distribution of environmental resources, environmental hazards, green infrastructure, or neighborhood amenities. My report inferred that access to governing and funding decision-makers played a critical role in gaining the power to execute plans. All partnerships spoke about the importance of supporting voices that have low influence but are high-impact communities, with their engaged environmental research projects.

NWF is in a unique position of influence due to its strong relationship with academic institutions and community organizations, to help build partnerships that can utilize community knowledge and academic expertise to develop practical long-term stewardship-based solutions. This post provides a short summary of my findings. I am thankful to all those academic and community members who participated in the interviews and shared their experiences with me. Thanks to this opportunity I am also developing a similar research project but focusing on the planning field, with the ACSP’s Diversity and Inclusion Scholarship.

Graduate Student Research Fellowships

Perhaps you or someone you know might be interested in serving as an NWF Graduate Student Fellow? NWF is currently accepting applications for 6 Graduate Student Research Fellowships.

Benefits of participation include:

• Earn a $6,000 stipend

• Play a key role in the development of NWF Education and Engagement Programs

• Gain valuable career experience and professional development

Application deadline is May 15, 2022.

Amruta Sakalker is a doctoral student in Urban Planning and Public Policy in the College of Architecture, Planning and Public Affairs (CAPPA) at the University of Texas at Arlington (UTA). At CAPPA, Amruta has successfully led collaborative research projects, which focus on building the regional stewardship capacity of communities and public/private agencies within the Dallas Fort Worth Metroplex for regional resources and amenities.

Through her studies around the complex relationship between land use, land ownership, and community behavior, she hopes to eventually provide communities, businesses, non-profit leaders, and government actors with actionable items that promote the wellbeing of watershed systems in urban areas. Her research focuses on planning and environmental policy initiatives that advance sustainable and equitable development.