We have much more to do and your continued support is needed now more than ever.

Seven National Wildlife Photo Contest Shark Pictures

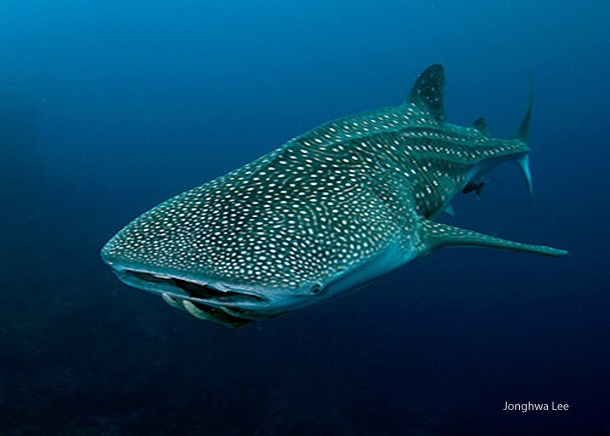

Although as an editor for National Wildlife magazine I’m accustomed to seeing some of the world’s best nature photography, I never cease to be amazed by the quality of work that participants enter in the annual National Wildlife Photo Contest. Excellent shots even of species that until recently were rarely photographed show up in the contest every year, such as the following pictures of great white sharks and whale sharks.

A Top Sea Predator

The white shark is perhaps the ocean’s most widely recognized predator, but it is still a creature experts know little about. However, new research is unlocking some of the mysteries of white shark behavior.

A growing body of evidence suggests that the world’s white shark population is broken into three units, one centered off South Africa, another off New Zealand, and a third, the northeastern Pacific population, that ranges between California and Hawaii.

A Killing Machine?

Studies off New Zealand indicate that white sharks are not born killers. The jaws of young sharks less than nine feet long are not strong enough for attacking large prey. Biologists working off California have found that the white shark’s diet changes with age, the animals often shifting from fish to mammals as they mature, but even that pattern is flexible—individual sharks tend to specialize in particular types of prey from a selection that includes seals, sea lions, dolphins, fish and squid.

Studies off South Africa and California reveal that sharks seek deeper waters when hunting. The dark upper body of the shark blends in with darker waters and ocean floors in coastal areas, allowing the hunter to lurk in spots frequented by seals and seal lions.

The Shark-Human Connection

Although great whites are coastal hunters, attacks on humans are relatively rare. In 2012, about seventy people were attacked by sharks of all kinds worldwide, with seven fatalities. About sixty percent of these attacks were on people lying on surfboards with hands and feet in the water—from the water below, they would resemble a seal. Often, after a first attack on a surfer, white sharks seem to realize their error and move on without a second attack.

Most sharks are harmless to humans. About half of the worlds’ approximately 360 shark species are less than 3 feet long; only 4 percent exceed 12 feet, and three of those feed on plankton, including the world’s largest, the whale shark—which at 30 feet long and about 5 tons is the largest animal in the world that isn’t a whale (the smallest shark is the pygmy ribbontail catshark, which grows to about 6 inches long).

Loss of sharks can have far reaching ecological and economic effects. Destruction of sharks in recent years along the U.S. Atlantic coast allowed cow-nosed rays to stage a population explosion; heavy feeding by the rays later caused a collapse in bay scallop fisheries.

Photo Contest

The 43nd annual National Wildlife Photo Contest is accepting this year’s entries through July 15. The contest is open to all photographers 13 years old and up and all levels of skill. The Grand Prize is a trip for two to Churchill, Manitoba, Canada to photograph polar bears,l in addition to which the contest offers $6,000 in other prizes.